Issac L. Rice House, 346 West 89th Street

by Tom Miller

Twenty-five years after Frederick Law Olmsted had planned the idyllic Riverside Park along Riverside Drive, it was finally completed. Imposing views of the Hudson River and New Jersey palisades, along with the pleasant green park, made residential lots desirable.

By the turn of the century, Riverside Drive was the Upper West Side’s answer to Fifth Avenue. Here, millionaire builders were less restricted, and along with the many upper-class row houses, there were no fewer than thirty free-standing mansions with lawns and gardens.

In 1899, the site for the planned Soldiers and Sailors Monument was chosen in the park at 89th Street. That same year, real estate developer William W. Hall sold the plot of land directly across from it to Isaac L. Rice for $225,000. The lot carried the restriction that anything built here must “be a high class private dwelling house, not less than four stories, and designed for the use of one family only.”

The New York Times chimed in on the purchase, noting that it “doubtless means the construction of a mansion that will be a fitting companion to the Clark residence on the opposite corner.”

Rice made a surprising choice of architects for his new residence, selecting Herts & Tallant, a firm that was making its mark as theater designers. Rice was familiar with their abilities, however, having seen their renovations of the Harmonie Club–actually their first commission—of which he was a member.

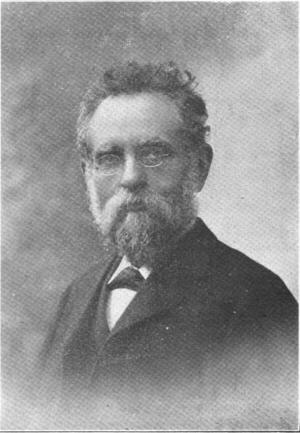

The German-born Rice had broad interests. While he made his fortune as legal counsel to railroad companies, most notably the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, he recognized the potential in electrical inventions and founded the Electric Vehicle Co., the Electric Boat Co., and was president of the Electric Storage Battery Co.

Rice founded the magazine Forum. It published insights, reviews and comments on political and literary issues. He was, as well, highly regarded nationally, as a proficient chess player, Rice invented an opening move known as the “Rice gambit.”

In 1905, she rallied the neighbors in a campaign to regulate the whistle-blowing.

If Rice’s choice of architects was unexpected, it was not regrettable. As plans were filed with the Department of Buildings in August 1900, The New York Times wrote, “Isaac L. Rice will build one of the finest mansions in the city…The French villa style of architecture will be followed…The exterior will be of brick and granite, with marble trimmings. In the centre of the structure an observatory tower will rise to a height of ninety-six feet above the curb.”

Deftly combining Neo-Georgian and Beaux-Arts styles, Herts & Tallant produced a red brick mansion trimmed in white marble, as The New York Times predicted. Four stories tall, it was accessed on the Riverside Drive side through a dramatic stone arch that rose through the third floor. Between the openings of the porte cochere, a carved bas-relief depicted six children with symbols of the Liberal Arts–possibly portraits of the six Rice children.

The mansion was completed in 1903, and the Rices entertained sumptuously. In keeping with their passionate interest in the arts, they held a dinner party for the French writer and lecturer M. Yves Guyot on December 27, 1904.

The luxurious mansion, named Villa Julia by Rice, and its beautiful setting, however, were not without problems. Tugboats passing on the Hudson below disturbed Julia Barnett Rice with their incessant horns and whistles. One purpose of the whistles was to summon crews from their late-night saloon visits. The intrepid Mrs. Rice would not stand for it.

Julia Rice held a medical degree from the Women’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary, an unusual accomplishment for someone of her sex and social stature at the time. In 1905, she rallied the neighbors in a campaign to regulate the whistle-blowing. Armed with petitions signed by hundreds of residents as well as the heads of several hospitals, she called upon Health Commissioner Darlington (claiming the noise “shattered nerves”), Police Commissioner McAdoo, Collector Stranahan, and other city officials.

The New York Times reported that ‘Mrs. Rice is prepared to lay the matter before Secretary Shaw of the Treasury Department if the city authorities find themselves powerless to remedy the matter.”

“Shattered nerves cannot be repaired,” she complained. “No reasonable person objects to the orderly use of whistles on the river or to continuous whistling on foggy nights when there is danger of a collision. However, there is no justification for the almost continuous blowing of tugboat whistles every night, which makes sleep impossible for hours at a time. It is a situation which rightly calls for protest, and the protest is not confined to the wealthy residents of Riverside Drive.”

The tugboat officers retaliated. Each night, a group of tugs would gather within range of Villa Julia, directing spotlights into the windows and blowing their steam whistles. It only steeled Julia Rice in her mission.

By November 1906, she had won her battle. “Unnecessary tooting” became a violation of the navigation laws. But Julia Rice was not done yet. Within a month, she had organized the Society for the Suppression of Unnecessary Noise and lashed out against noise in the vicinity of hospitals. “I have been informed that in some instances, patients have been driven insane by these unnecessary noises,” she claimed.

Armed with a gramophone and recordings of street noise, she invited reporters into her library to listen to what The New York Times called “the whirr and bang of flat-wheeled surface cars, the shriek and rumble of the elevated expresses, the honk of the automobile, and the various discordant street cries, tooting of whistles, yell of street vendors, etc.”

Today’s quiet zones around hospitals owe their existence to the fervent struggles of Julia Rice.

In February 1906, Mrs. Rice hired a young servant girl, Hortense Uzac, who had just arrived in New York from her native France. Three weeks after the maid had begun work, Julie Rice left her bedroom around 10:00 at night to attend to a reception downstairs. She failed to lock the bedroom door.

Half an hour later she returned and noticed a ring that had been on her dresser was missing. A few days later, as Detective Moran was questioning the servants one by one in the parlor, the girl bolted from the house and threw herself into the icy Hudson River. She was pulled out and arrested for attempted suicide. Julia Rice reacted with kindness and sympathy.

“There was no accusation of any sort against the Uzac girl,” she insisted, “unless the police may charge her with attempting to take her life.” The ring was found in a search of the house. “Nothing else is missing and no accusations of any sort are made by us,” she said.

Isaac Rice, by 1907, was president of the Holland Torpedo Boat Company, a position that required him, along with Julia, to spend extended periods of time in Europe. They decided to sell Villa Julia.

In December 1907, it was sold to cigarette manufacturer Solomon Schinasi for $600,000. In reporting the sale, The New York Times noted, “The Rice house, with its grounds, modeled after an Italian villa, has long been one of the show places along Riverside Drive.”

Schinasi, said The New York Times, “will occupy the house as soon as extensive alterations can be completed.” The “extensive alterations” included an extension at the southeast corner and a semicircular bay. Mansion architect C. P. H. Gilbert designed the renovations, melding them seamlessly with the Herts & Tallant architecture.

a developer offered between $1.5 and $2 million for the property as the site of a 30-story tower-plaza building…

In 1912 Gilbert was brought back to design a new brick and marble wall around the property–the original having been ordered demolished as it extended beyond the property wall. Gilbert mimicked the balustrades of the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial across the street, creating a harmonious flow.

Schinasi died in the house of heart disease on October 4, 1919. Eight years later his son Leon added a garage and an additional story to the bay extension, all in keeping with the original architectural design.

Ruby Schinasi remained in the house after Leon’s death. In 1935 the wealthy widow reported spending $30,000 annually on each of her two children, Solomon, then eight years old, and Betty, six.

Change came in 1954 when the Yeshiva Chofetz Chaim acquired the mansion. The building was a blessing and a curse to the cash-strapped religious school for Jewish children. While the yeshiva attempted to maintain the structure, costs were always an issue.

So when, in 1980, a developer offered between $1.5 and $2 million for the property as the site of a 30-story tower-plaza building, good fortune seemed to shine on the school. A battle between the school and preservationists quickly developed. Facing the school across the battle lines were high-powered names like Jacqueline Onassis and Itzhak Perlman. It would be one of the fiercest and most harrowing landmark battles in the city.

The Landmarks Preservation Commission was charged with proving that the mansion possessed special character, special historical or aesthetic interest, or value.” Rabbi Feigelstock of the yeshiva didn’t think it did. “By me, Isaac Rice is not anybody,” he said.

Whether Rice was anybody or not, the house was determined to be a landmark and the yeshiva was stuck with it.

By 2005, it was becoming degraded. Now home to Yeshiva Ketana, its decorative copper was falling away, the balustrade wall was cracked and deteriorating and neighbors complained regularly that Julia Rice’s Italian gardens were now a dust bowl, filling their homes with dirt on windy days.

The mansion remains in the hands of the yeshiva, which tries valiantly to keep the property in repair. It is one of two surviving freestanding mansions on Riverside Drive and a lovely, if tattered, reminder of better days.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com