340 West 85th Street

by Megan Fitzpatrick

Jane Harriss Hall, a Deaconess at St Mark’s Church, founded the Three Arts Club after she noticed the benefits of holding a social club in the evenings for students at her church. She also experienced many young women coming to her looking for reasonable accommodation for a student in the city. Decent accommodation that was safe, clean, and cheap was hard to come by during this period right before the rooming house boom. However, the demand for accommodation for single-working women was on the rise in the early 20th century and women’s only buildings became more and more prevalent in the city.

Hall took inspiration from an existing club in Paris, the American Girls’ Club, and this model also found its way to other U.S. cities like Chicago, which had The Chicago Three Arts Club, founded in 1912.

The New York Three Arts Club was founded in 1903 under the auspices of the Protestant Episcopal Church, though the group was non-sectarian. They first met in a small house on West 56th Street (American Art News, 1904).

The first clubhouse was located on the corner of 62nd Street and Lexington and could accommodate about 33 “resident member” students, but was forced to turn away around 80 (American Art News, 1904). With Club membership growing to 100 students taking classes, and each out-of-town student desperately looking for inexpensive housing, the Club decided on a new move.

Several benefits were held to fundraise the money to move to a larger premises. In 1907, Mrs. John Henry Hammond held a benefit at her home at 9 East 91st Street to fundraise in part towards purchasing two buildings on the Upper West Side for Club purposes, 532 & 536 West End Avenue (New York Times, February 20, 1907). Emily Vanderbilt Sloane, better known by her married name Mrs. Hammond, was president of the Club for 43 years. An ardent philanthropist, Mrs. Hammond was the daughter of William D. Sloane, granddaughter of William H. Vanderbilt, and great-granddaughter of railroad magnate Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt. She used her place in society to advance the lives of young women in their pursuit of the arts (New York Times, February 23, 1970).

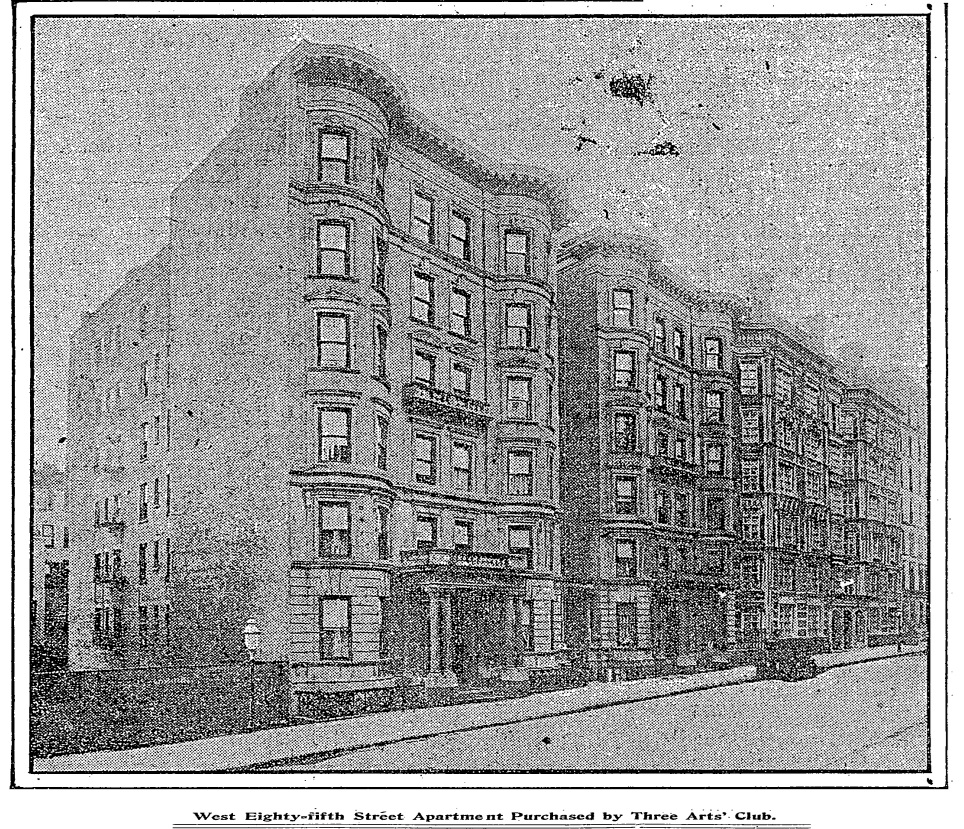

A year later, they were set up in their West End Avenue buildings but still needed to fundraise to purchase the buildings, as the rent was too high (New York Times, April 26, 1908). However, in 1909, “having outgrown its present quarters at 536 West End Avenue” the Club decided to move into an elevator-operated apartment house at 338 and 340 West 85th Street (New York Times, November 28, 1909).

The purpose-built clubhouse featured apartments for members, a stage and auditorium, art studios, exhibition rooms, and a wood-paneled library gifted by Frederick Vanderbilt and named Louise Anthony Vanderbilt Library

The Club attracted the attention of well-known women and philanthropists in New York Society who saw it as an opportunity to encourage young women’s ambitions for the arts in a safe, clean, and inexpensive environment in the city. Many benefit concerts and performances were arranged by the clubhouse to not only showcase the talents of its members but to fundraise its organizing.

Theodore Roosevelt had strong links to the clubhouse, and its president, Mrs. Hammond. In 1912, Theodore Roosevelt was the guest of honor at a reception at the clubhouse where 300 guests attended and had the opportunity to shake the former president’s hand. Roosevelt and the then President William Howard Taft, were named as honorary patrons of a benefit performance that same year at the Republic Theatre (New Victory Theatre) organized by the Club (New York Times, January 20, 1912). Mrs. Hammond was also the president of the Women’s Roosevelt Memorial Association and would go on to restore the birthplace of Theodore Roosevelt at 28 East 20th Street in the early 1920s (New York Times, February 23, 1970).

The Club would often hold receptions for skilled artists of their crafts, in stage and screen, and have hosted coloratura soprano Madame Lily Pons, following her U.S. debut at the Met in 1931, and actors Leslie Banks and Nigel Bruce (New York Times, February 27, 1932).

Due to the growing demand for the Club and its residences for young women, a new space was needed. Instead of looking elsewhere in the city, the Club’s committees decided to demolish their current home and build a purpose-built clubhouse, in the same ideal spot, less than 250 feet from Riverside Drive.

In 1926, the Club mortgaged their building for $280,000 with the intention to demolish it “because it is inadequate” for their current needs, as reported by the New York Times (June 16, 1926). The Club recruited architect George Bruno de Gersdorff to design it.

George Bruno de Gersdorff was born in Salem, Massachusetts. After attending both Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the late 1880s, he continued his education at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, France. Upon his return to the United States, he entered the offices of McKim, Mead & White. De Gersdorff is most well known for designing the first concrete football stadium in the U.S. in 1903 for Harvard, his alma mater.

De Gersdorff designed an eight-story red brick building with an unmistakable Colonial Revival style, complete with a high stone water table base and arched central entrance flanked by two Corinthian columns on the ground floor. At the second floor level, a center bay window with an ornamented scroll bracketed sill and iron balconette sits above the sign for the name of the residence club, “Three Arts Club.”

The purpose-built clubhouse featured apartments for members, a stage and auditorium, art studios, exhibition rooms, and a wood-paneled library gifted by Frederick Vanderbilt and named Louise Anthony Vanderbilt Library, in honor of the memory of his wife. The main issue with the previous building’s design was the lack of communal spaces for members of the Club, therefore ample spaces like a dining hall, cafeteria, and lounge were designed and even a small addition was built on the roof, used as a workshop (New York Times, November 13, 1927).

The new clubhouse officially opened its doors in November 1927 and could accommodate private rooms for 153 students, with a long list of applicants.

Several socialites in the city attended the opening ceremony despite the pouring rain, and addresses were given by founder Jane Harris Hall, de Gersdorff, and composer Walter Damrosch (New York Times, November 18, 1927).

Not long after the new building opened, tragedy struck the Three Arts Club. Club member, Margaret Appleton Means, known by her married name, Mrs. Charles Thomas Payne, jumped from the living room window of her 7th-floor apartment at 114 East 71st Street. She had been undergoing treatment in a sanatorium in New Jersey, suffering from “a nervous breakdown,” and was spending the day away in the city, accompanied by her nurse, Edith Russell. Her late husband’s colleagues recounted her day to the police, “In the morning, Mrs. Payne went to the office of a New York occultist for treatment. She then lunched with Miss Russell at a restaurant, and after returning to her apartment, apparently in high spirits, she told the nurse to take a walk” (New York Times, August 20, 1931).

The superintendent found Mrs. Payne, at the bottom of a short flight of wooden steps leading from the 71st Street sidewalk to the basement service entrance. She was a socially prominent member of New York society, keenly interested in artists’ endeavors, and was a close friend of Mrs. Hammond (New York Times, August 20, 1931).

The Arts Club started as a place for Upper-class women to express their interests and gain a bit of freedom, supported by well-to-do philanthropists. However, as the decades progressed, it became not just a place for young, accomplished socialites, but women came from all different states and all different backgrounds, mostly white women, to take up cheap accommodation at the Club.

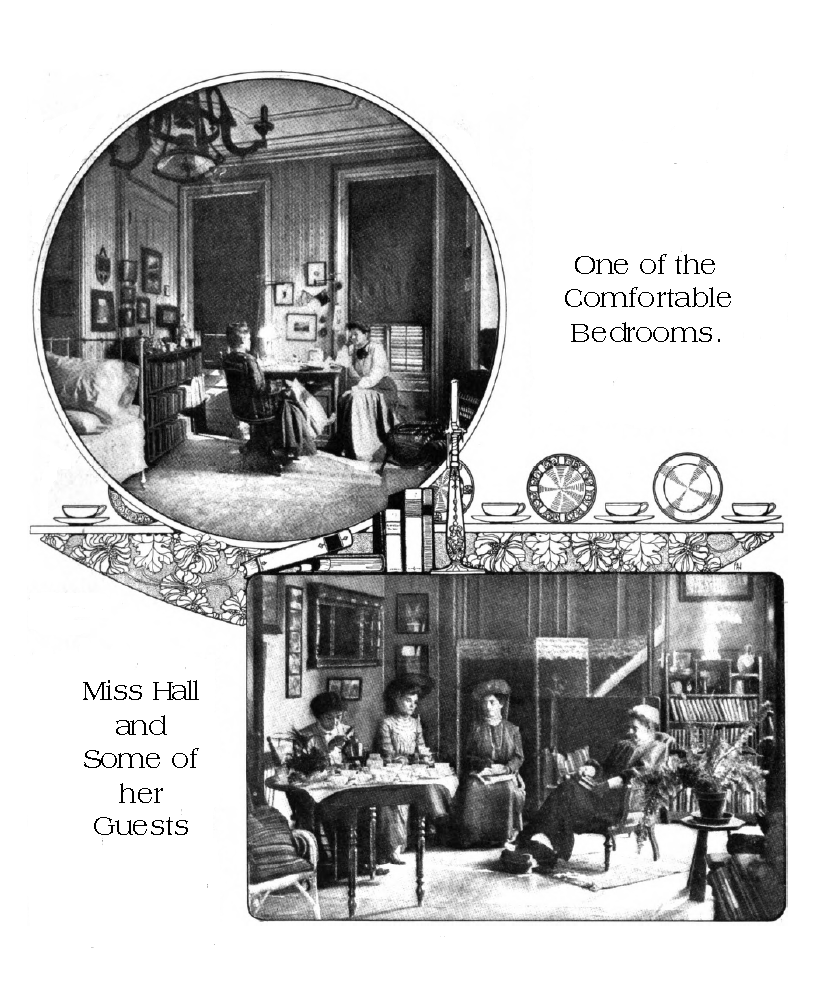

When it first opened, rent was a nominal sum of $3 – $5 a week (Designer, 1905). When dancer Sybil Shearer lived at the Club in the 1930s, rent was a “very reasonable $12 a week for room and board, except weekday lunches” (Without Wings the Way is Steep, Sybil Shearer, 2006). Resident members soon would share rooms instead of individual private rented rooms, as it started, presumably to match rising demand.

It can be ascertained through former members’ testimonials that a residence for young artistic women became quite the hot spot in town. Set designer Betsy Hall lived at the clubhouse in 1931 and said, “Whenever there were extra tickets for a ballet or a performance at the Metropolitan Opera, some kind impresario would leave them at the Three Arts Club for the girls” (Democrat and Chronicle, February 4, 1968).

Many artists well known to us today lived at the clubhouse. Aspiring writer Fannie Hurst came to New York just before WWI, a struggling newcomer, who moved around a lot trying to find work and decent accommodation. She found herself in a bad neighborhood, and when police raided her apartment building, her mother, who knew Deaconess Hall, suggested she move to the Three Arts Club, describing it as a “wonderful place for girls in New York…it is difficult to get in. There is always a waiting list.” She let it be known to her daughter that you must be studying dramatic art or music to quality, but says Hurst played music at “Keith’s” so she should be fine (Anatomy of Me, Hurst, 1958).

Unfortunately, for Hurst, this was not sufficient. She was asked to leave the Club after she sold her first story in the Saturday Evening Post as it exposed her as an author, which disqualified her from seeking accommodation at the Club. “You evidently entered under false premises as a dramatic artist,” the manager of the clubhouse said. Despite the strict definitions of ‘artist’ employed by the Club, Hurst would go on to write many best-selling melodramas (Back Street) and find herself an apartment within the Artists’ Colony of West 67th Street at the Hotel Des Artistes (Upper West Side Story, Salwen, 1989).

Whereas Hurst was rejected from the clubhouse, actor and screenwriter Ruth Gordon excelled while living under its roof. Although she remarked to a former club mate, actor turned gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, how the two lived as starving artists while they lived at the Club, she gained critical acclaim for her work and became an award-winning actor, screenwriter, and playwright. In 1946, Gordon wrote an autobiographical play named “Years Ago,” where she dramatized convincing her father to let her pursue acting in New York. In it, she says someone referred her to the Three Arts Club and Gordon reserved her room before she had even arrived in New York. Her mother described the club as like a Y. W. C. A, but “far superior” (Years Ago, Gordon, 1946).

Te Ata, also known as Mary Frances Thompson Fisher, was a Native American actor, and a member of the Chickasaw Nation. Her teacher, Frances Davis, arranged for Ata to live at the Three Arts Club when she moved to the city to pursue theater. Although she only lived there for a year, she attributed her early success to her time at the clubhouse. In 2002, her biographer, Richard Green, wrote, “Resembling a college dormitory for young women trying to break into one of the arts, the Club offered numerous benefits to the residents. By living together, they could socialize and through shared experiences help each other learn the ropes. “We gave each other tips that so-and-so was booking for a play and needed a certain type of person” Te Ata recalled.”

She described how the women of the clubhouse took the timid Te Ata under their wing and would always go to booking agencies together as a group and how that gave them a sense of confidence “that none of them could muster alone.” Some Clubwomen became early benefactors of Ata, such as Anne Tucker, wife of wealthy industrialist Samuel Tucker, and Ata referred to her as housemother. Although none of the society matrons lived at the club, it reveals how invested women in high society were in the pursuits of these talented young artists (Te Ata: Chickasaw Storyteller, Richard Green, 2002).

When dancer Sybil Shearer lived at the Club in the 1930s, rent was a “very reasonable $12 a week for room and board, except weekday lunches”

Not much is known about the downfall of the Three Arts Club. Records show that in 1952, a “syndicate” bought the building, valued at $400,000. Mrs. Hammond was still the president of the Arts Club at the time of the sale. We cannot be sure if the Club continued at another location in New York or ceased to exist entirely.

Ruth Gordon returned to the clubhouse in 1956 to pay a visit following her success in the Broadway production of The Matchmaker, and a few years after the Club was no longer at this location. Gordon asks the woman at the front desk, “I’m Ruth Gordon, I used to live here,” after which the woman leafed through the Three Arts Club ledger until she found the entry, “Ruth Gordon, 14 Elmwood Ave., Wollaston, Mass.” She looked up brightly and asked, “Same address?” (Daily News, September 16, 1956).

Shortly after the sale of the building, the Volunteers of America moved in and established The Brandon Residence, supportive housing for single women. A black “Volunteers of America” sign was placed over the historic “Three Arts Club” engraving.

The building was bought in 2017 by the West Side Federation for Senior and Supportive Housing, with plans to convert it to senior housing. The “Three Arts Club” sign above the entrance has been faithfully restored.

Megan Fitzpatrick is the Preservation Director of LANDMARK WEST!