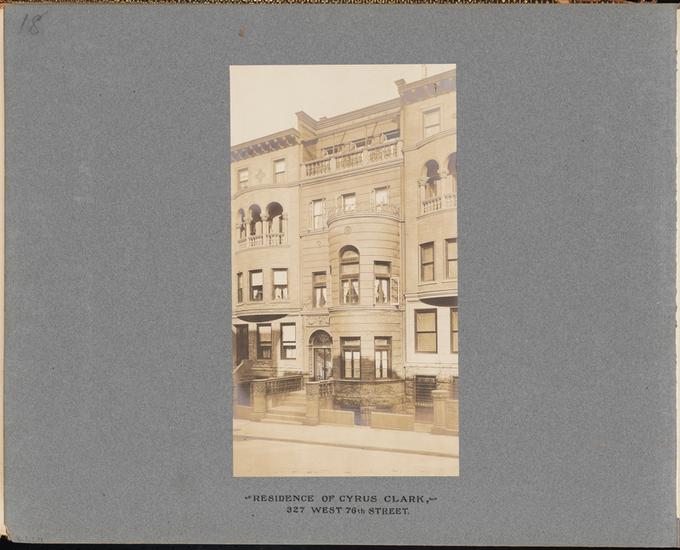

327 West 76th Street

by Tom Miller

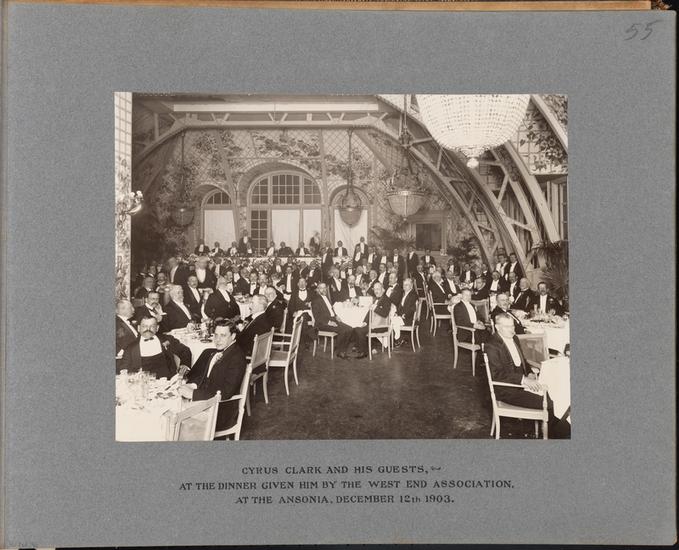

On December 12, 1903, the West End Association gave a dinner in honor of Cyrus Clark, whom it called “The Father of the West Side.” The tribute could not have been more appropriate.

While still in his 30s, Cyrus Clark had amassed a fortune and retired from the wholesale silk business. After traveling throughout Europe for three years to study real estate administration, he returned to New York in 1870 and began purchasing land in the relatively undeveloped Upper West Side.

Clark became president of the West End Association and lobbied tirelessly for the development of the area. He was one of the original proposers of Riverside Drive, worked to have gas street lamps installed along 9th Avenue, and extended the rapid transit system to the area.

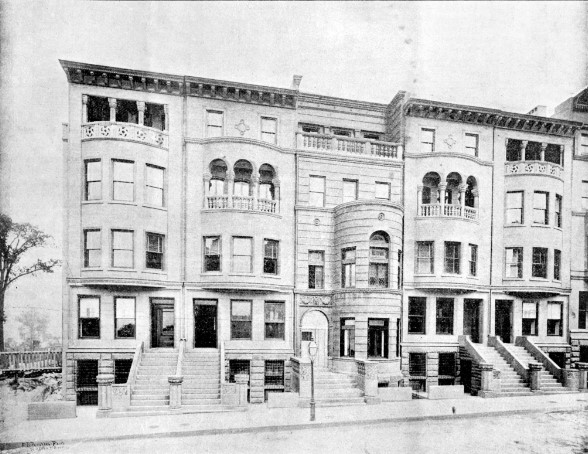

By 1898, the side streets of the Upper West Side were becoming lined with rowhouses for upper-middle-class families in architectural styles far more adventurous than anything on the East Side. Clark purchased the newly completed No. 327 West 76th Street that year; one of a row of harmonious homes stretching from No. 323 to 331 built on speculation.

Senator Grady proposed establishing two piers at the foot of West 96th Street and West 79th Street “as dumps for ashes, garbage and other refuse.” Cyrus Clark went into action

The Architectural Record made note of the row. “They mark as distinct an advance from the brownstone front as that marked a distinct retrogression from the still ‘Colonial’ house of the second decade,” it said. “Nos. 323-331 West Seventy-sixth are particularly interesting. Too strong a differentiation is made by using red brick entirely for the central house [the Clark house], while the flanking houses are of brown stone with some admixture of brickwork. But the differentiation is mainly managed by the difference in the position and treatment of the loggia.”

The publication hesitated on this point, reflecting that the picturesque balconies were perhaps less functional than quaint. “Perhaps the loggia is more theoretically than practically a desirable adjunct of the city house. For while it would be as useful as it is agreeable in a house that was lived in all the year, it is evident that the inhabitants of houses of this class abandon them at the season when the loggia would be a pleasant resort. But of the utility of it as an architectural device, as it is used here, there can be no manner of question.”

The same year that Clark moved into his new home, Senator Grady proposed establishing two piers at the foot of West 96th Street and West 79th Street “as dumps for ashes, garbage and other refuse.” Cyrus Clark went into action.

He gathered reporters in the parlor of his new home. “We shall fight this proposed amendment vigorously,” he told them. “Riverside Park is well known to contain one of the finest driveways in the world and it seems strange to me that after the city has expended nearly $7,000,000 for the purpose of beautifying this park that there should be any question about $25,000, which is the annual expense necessary for hauling the ashes of this district to some more remote locality.”

Cyrus Clark got his way and a site was found for the dumps far from the West Side.

In May 1909, while working to have mortgages exempt from taxation, he became ill. Within two weeks he had become paralyzed and on May 24 he died at his home on West 76th Street, leaving what the New York Tribune called “a considerable fortune” to his two sons and three daughters.

Within a year, the West End Association filed a request with the Park Commissioner to erect a monument to Cyrus Clark. Unveiled in 1911, the $2,000 monument consisted of a bas-relief bronze plaque set into a natural boulder in Riverside Park.

Five months after Clark’s death, the house at No. 327 West 76th Street was sold to Virginia-born Henry Clay Adams. Mrs. Adams was highly visible in society and a month after moving in she hosted a tea for the Adams’ niece, Dorothy Fox as part of her introduction to society.

Perhaps her most fervent activity each year was her participation in the organizing of the annual charity ball at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. In 1914, the $5 tickets could be obtained at her house for the event which The New York Times labeled “the oldest social function in New York, if not in the country.”

That year she told The Times that the sale of tickets for the ball, which would have three bands, had not only been very promising, but “almost unprecedented.” The newspaper projected this was due “perhaps to the present fascination for dancing.”

The $5 tickets could be obtained at her house for the event which The New York Times labeled “the oldest social function in New York, if not in the country.”

By 1920, the Adams family was gone and Alberto Bimboni lived here, coaching blossoming opera singers from his “vocal studio.”

Like so many of the large, Upper West Side residences at mid-century, No. 327 was converted to six apartments in 1950. Within a few years, the Tucson Fine Arts Association established its New York City offices in the house. For decades, much of the groundwork for the annual Aspen Music Festival was laid here.

From 1960 until a year before her death in 1973, artist Ann Kocsis worked from the house as secretary of the Tuscon Fine Arts Association.

The handsome block of houses, including No. 327, remain, as the Architectural Record said in 1899, “equally unaffected and straightforward expressions of the conditions of New York life, whether or not they wear the badges of some historical style.”

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com