262 Central Park West

by Tom Miller

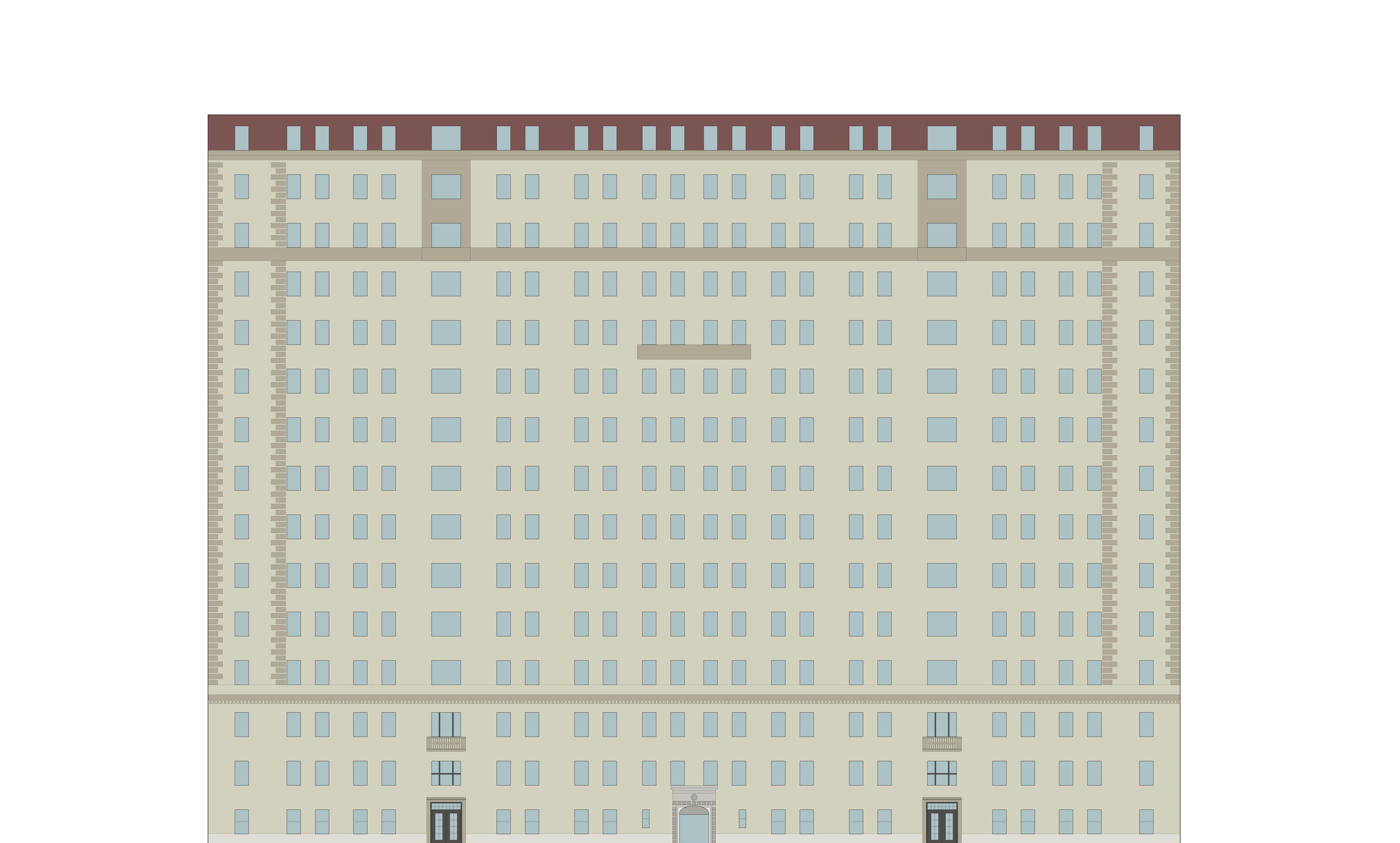

In 1927 Sisbrothers, Inc. hired the architectural firm of Sugarman & Berger to design an apartment building that would engulf the Central Park West blockfront from 86th to 87th Street. Unlike the modish Art Deco style buildings rising along the park at the time, the architects turned to the more traditional Italian Renaissance for 252 Central Park West. The 14-floor structure was completed the following year.

In May 1928, three months before construction was completed, an advertisement read in part, “Facing the beautiful, broad acres of Central Park for a full city block…262 Central Park West represents the highest development of modern apartment house building. Its construction and appointments are a revelation to the discriminating.” At the time of the ad, 55 percent of the apartments had been rented. Potential residents chose among apartments of six, seven, eight or nine rooms, with three or four baths. There was also a “special penthouse apartment” of nine rooms, with four baths and an “extra lavatory.”

The building filled with well-to-do tenants, like the Irving Miller family. Born in Poland in 1873, Miller came to New York City at the age of 19. A cobbler, he fashioned shoes for theatrical productions. Soon he was not only designing shoes for plays but for the thespians and vaudevillians who flocked to him for their personal footwear. Within just three years, he opened the I. Miller shoe business.

In 1929, the same year that he and his wife Annie moved into 262 Central Park West, he erected his flagship store on Times Square (there were three other stores in Manhattan and one in Brooklyn). He and Annie had four sons, George, Michael, Maurice, and Charles. The name of the business was now I. Miller & Sons, and it was a favorite of fashionable women shoppers.

Louis and Bessie Adler were also early tenants. Bessie was the daughter of Julis and Lena Miller (apparently no relation to the Irving Millers). Several of her extended family also lived in the building. When her father’s estate was settled in June 1932, The New York Sun mentioned that among the beneficiaries, along with Bessie, were Julius Miller’s grandson, Seymour Klein; his brother-in-law Alexander Zinke and nephews William and Irving Zinke, all of whom lived at 262 Central Park West.

Fearing possible detention or worse, on the morning of January 7, 1943, the 50-year-old wrote a note to Lucy Blumenthal, and then leapt out the window to her death.

Sidney Blumenthal and his wife, the former Lucy A. Picard, were married in France in 1903. They moved into the building upon its opening. Blumenthal was president of Sidney Blumenthal & Co., a textile manufacturer founded by his father. He had entered the business in 1879 when it was still called A. & S. Blumenthal and was making silk ribbons. The couple had a son, Andre, and two daughters, Doris and Yvonne.

Residents of the building had live-in domestic help. When Sidney and Lucy A. Blumenthal moved into their 12th-floor apartment in 1929, they hired a German-born maid, Jennie Daasch. Twelve years later, she began the process of becoming a United States citizen. She panicked after the country became engaged in war with Germany. On her application, she had failed to declare her German property. Whether the omission was purposeful or accidental is unclear, however it began to prey on her. Fearing possible detention or worse, on the morning of January 7, 1943, the 50-year-old wrote a note to Lucy Blumenthal, and then leapt out the window to her death. The note read, “You know the reason for my doing this. It is the best way out.”

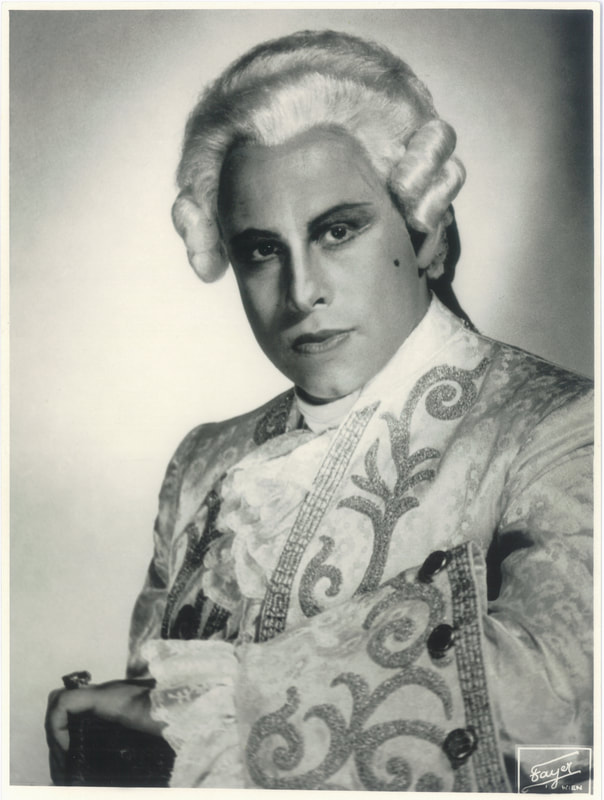

In 1957 George and Nora London moved in. In her 2005 book George London, Of Gods and Demons, Nora describes “a wonderful apartment with three large bedrooms, a library, and huge living and dining room. All of this was surrounded by a wide terrace with a magnificent view of Central Park.” The couple filled the apartment with art. “There were a number of paintings by the French painter Maclet representing scenes from Paris, and George soon bought some Chagall lithographs, an Italian sculpture representing Don Quixote, and a Chinese bronze Kuan-Yin.”

Born George Burnstein, London was a concert and operatic bass-baritone. He and Nora Schapiro were married in 1954. The year they moved into 262 Central Park West, London opened the season at the Metropolitan Opera and did so again the following season. According to Nora London, the years they spent at 262 Central Park West—1957 to 1964— “spanned the most successful years of George’s singing career internationally, and above all, at the Metropolitan.” That last season, 1963-64, London was diagnosed with a paralyzed vocal cord. His last appearance at the Met was in March 1966, and his career ended in 1967 at the age of 46.

The building achieved a moment of cinematic fame when it was the scene of the apartment of Natalie Wood’s character, Marjorie Morningstar, in the 1958 motion picture of the same name.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Abraham Michael Rosenthal (who went professionally by A. M. Rosenthal) and his second wife, Shirley Lord, lived here by the late 1980s. Born in Canada in 1922, he was brought to New York as a child. He worked his way up at The New York Times until achieving the post of executive editor. In his 2023 book The Times, Adam Nagourney recounts:

Clerks and copyboys were assigned to attend to his needs, professional and personal, which included ferrying his briefcase to his penthouse at 262 Central Park West…Another of Rosenthal’s clerks, Richard J. Meislin, juggled the personal and professional needs of the editor. One day, Meislin would be calling the Brooklyn Botanic Garden to inquire about the ailing Japanese black pine tree Rosenthal had installed on his penthouse terrace. Another, he was carting bricks and dirt up to the rooftop garden.

The Rosenthals were still living here when the editor died at the age of 84 on May 10, 2006.

Famed violinist, composer, and conductor Robert Nathaniel Mann and his wife Lucy Rowan lived here by 1973. Born in Portland, Oregon in 1920, Mann intended to be a forest ranger, but his musical talents got in the way. At the age of 18 he was accepted into the Julliard School and in 1941 he made his New York debut. He was drafted into the U.S. Army shortly afterward.

In 1946, after serving in the war, he joined the Julliard faculty, and that year founded the Julliard String Quartet. He served as its first violinist until his retirement from the quartet in 1997. Robert Mann died on January 1, 2018 at the age of 97.

One day, Meislin would be calling the Brooklyn Botanic Garden to inquire about the ailing Japanese black pine tree Rosenthal had installed on his penthouse terrace. Another, he was carting bricks and dirt up to the rooftop garden.

Toni Greenberg moved into the building in the mid-1970s. She was the widow of Noah Greenberg, the founder and musical director of New York Pro Musica. A philanthropist and arts patron, she was assistant to the president of the Mannes College of Music from 1966 to 1970 and was acting director of the New York University Institute for the Humanities beginning in 1970. Toni Greenberg lived here until her death at the age of 65 on December 4, 1990.

Unlike many apartment buildings on the West Side, 262 Central Park West was not named. That changed when the building was converted to a cooperative and was christened The White House.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

RETURN TO CENTRAL PARK WEST

BUILDING DATABASE