256 West 75th Street

by Megan Fitzpatrick

The West End Association was originally founded in 1884 by William Earle Dodge Stokes and other developers as the Citizens’ West Side Improvement Association. They labored to improve the area around West End Avenue by lobbying city and state governments and ultimately developing it into the quiet residential neighborhood it is today rather than the envisioned commercial hub of small shops. Stokes is best known as the developer of the Ansonia Hotel on Broadway, however, before that he hired a series of rising architects and builders to design and construct his rowhouses on the Upper West Side.

American-born architect William J. Merritt and his construction company were frequent collaborators of W. E. D. Stokes and their constructions on West 74th and West 75th Streets are some of the most significant rowhouses on the old Upper West Side. They were some of the earliest dwellings erected in the neighborhood and therefore set the precedent for that era of construction.

Merritt applied an eclectic, yet repetitive, style to most of his three-story dwellings that allowed for a flurry of rowhouse construction within a few short years on the west side. Critics would describe his style of facade construction as a “Reign of Terror” inflicted on the West Side, and a contemporary “eminent” architect detailed how the growing trend of individualized “sixteen-foot fronts” Upper West Side dwellings “made him sea-sick” (Zabar, 1977; Architectural Record, 1899).

Nevertheless, these three-story rowhouses grew in popularity because of their affordability, as opposed to the expensive townhouses across the park. This was mostly due to their shortened lot size and the rapid construction of housing at a low cost on the mostly unused land of the West Side. As the Architectural Record stated in 1899, “the West Side seemed to offer the small New Yorker his chance”. Additionally, title insurance on properties was introduced as a novel idea around the period. The Real Estate Record and Builder’s Guide notes in 1885, “the property offered should be sold with title insurance. The same principle had been applied with the same results to improved property both on the floor of the Exchange and at private sale. A notable recent example is the rapid sale of the fifteen houses on Seventy-fifth street, now being offered by Mr. W. J. Merritt, who tenders with his deed at his expense a title pottery of this company, guaranteeing the purchaser to the amount of the purchase price”

One of these properties was Stokes and Merritt’s row of two, three-story rowhouses on West 75th Street, just off West End Avenue, filed in 1885. Although both rowhouses did not appear alike, they shared a quintessentially eclectic Queen Anne-style facade with rusticated stone bases, decorative paneling, and curved oriel windows. No. 256 featured a dormered roof and off-centered pediment, a further nod to the Queen Anne style.

Critics would describe his style of facade construction as a “Reign of Terror” inflicted on the West Side

It was no “small New Yorker”, however, who purchased 256 West 75th Street when it went on the market in 1886. The first owner was Elizabeth Van Schaick Winthrop (neé Oddie). Elizabeth married into old New England money. She married Grenville Winthrop in June 1861 and they had four children, Mary, Isabel, Alida, and Grenville B. Winthrop. Grenville could trace his family directly to the Winthrops of England, the first settler founders of Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. His brother was the wealthy banker and capitalist Robert Winthrop, and his nephew was influential art collector Grenville L. Winthrop. They were a well-established family in Manhattan.

Grenville, Elizabeth and their family would travel to England and France often and it was on one of these fateful trips to Pau in the Aquitaine region of France where Grenville tragically died in 1869, leaving Elizabeth a widow.

If Elizabeth ever lived at 256 West 75th Street, it was not for very long. Although she was listed as its owner, early records never show her or her family as occupants. Instead, a long list of lessees occupied the dwelling under the Elizabeth V. S. Winthrop Estate.

The earliest lessees were middle-class New Yorkers such as Augustus W. Cruikshank and his wife who would host tea parties in the parlor and Thomas Purcell, first-generation Irish immigrant broker, and his family.

Around the mid-1920s, the dwelling was split into apartments. In the 1925 census records, most of the residents identified themselves as working class. Many occupants worked cleaning jobs, possibly for their wealthier neighbors on the Avenue.

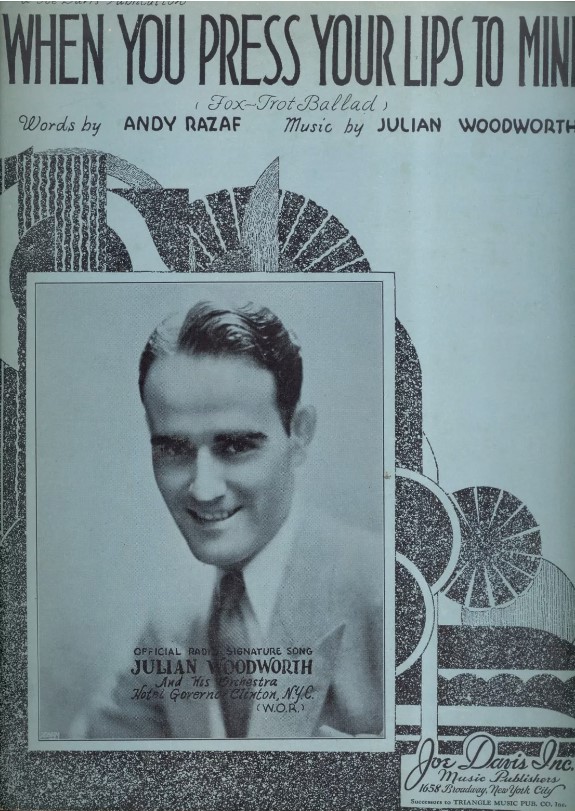

Some notable roomers were musicians James Liebling, a cellist who was named one of the best in the country during this decade, and Julian Woodworth, a pianist, composer, and lyricist. Woodworth moved into the apartment around 1940 and it was during this time his career began to expand. He composed his most well-known piece in 1931 called When You Press Your Lips to Mine in collaboration with Harlem-based poet and lyricist Andy Razaf.

In 1952, the rowhouse finally exchanged hands. Many changes had occurred to the dwelling since it was first constructed, although remarkably, it had been owned by the same family, the Winthrop Estate, since 1886.

Many occupants worked cleaning jobs, possibly for their wealthier neighbors on the Avenue

When the West End Collegiate Historic District was designated in 1984, W. E. D. Stokes and William J. Merritt’s rowhouse was excluded from the district. However, 254-256 West 75th Street, as well as their other rowhouses on West 74th and 75th Streets were finally acknowledged in 2013 when the Historic District Extension was made.

The early-built fabric of the rowhouse has remained relatively intact. However, some alterations occurred, namely the removal of the dormer roof and pediment above the cornice. In 2019, a permit was approved by the LPC to restore the dormer roof and pediment to its original appearance.

Unfortunately, some alterations went too far, including the installation of a glass-paneled door without approval from the City agency.

Megan Fitzpatrick is the Preservation Director of LANDMARK WEST!