The Rossleigh Court

by Tom Miller

On August 4, 1906, the Record & Guide noted, “Famous as a thoroughfare of fine apartment houses, Central Park West is seeing in the present more improving work than at any period in its history since the movement attending the building of the elevated railroad.” In enumerating the many projects taking shape, the article said, “On the south corner of 86th st. the Gorham Building and Construction Company is erecting a 12-sty apartment that will cost $950,000, exclusive of the land, from plans of Milliken & Moeller. Excavating has commenced for another elevator apartment house on the north corner of 85th st.”

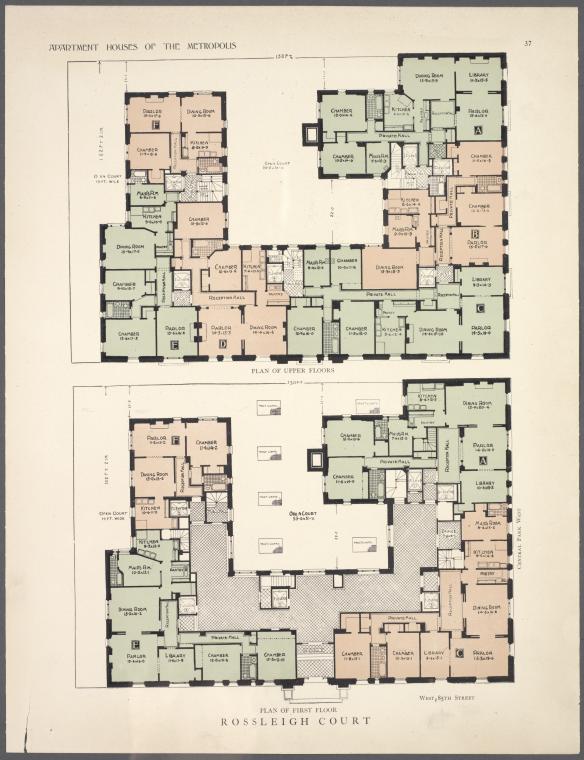

The second building mentioned was built by the same developers and designed by the same architectural firm. In fact, it would be a back-to-back duplicate of the 86th Street structure. Completed in 1907, the 12-story Rossleigh Court, like its identical twin, sat on a two-story rusticated limestone base. The red brick upper floors were adorned with Beaux Arts style balconies and lintels, and stone quoins ran up the corners and defined the two buildings. The entrance was placed to the side at 1 West 85th Street.

The apartments ranged from four to eight rooms, with one or two baths. An advertisement boasted that they “are equipped with every modern convenience.” Perhaps the most innovative of those was the mail delivery system. Small elevators, similar to dumbwaiters, carried mail and small packages directly to each apartment. The advertisement said, “Kitchens are wainscoted with marble five feet high; porcelain tubs and sinks, nickel plated plumbing, and garbage closet. All water from public main is filtered in building.” Each apartment had a wall safe, and a central vacuum-cleaning system. Service elevators guaranteed that deliverymen and servants did not mingle with guests and occupants.

Rents ranged from $1,700 to $3,100 per year or about $7,680 per month for the most expensive in today’s money. The extraordinary rent covered the best apartment in the building. Its rooms centered around a 14- by 19-foot parlor with corner views. On one side was the dining room with a fireplace, and on the other, the library. Three bedrooms branched off a long hallway.

Among the initial residents were Morris Schinasi and his wife Laurette. A native of Manisa in Asia Minor, he and his brother Solomon imported Turkish tobacco and produced cigarettes under the brand name “Natural.” When the couple moved in, he had amassed millions of dollars. Their occupancy would be short-lived, however. Their free-standing mansion at 351 Riverside Drive was already under construction, and they moved into it in 1909.

Moving into the Rossleigh Court that year was Estelle Christy, known as “the perfect chorus girl.” She had recently made headlines worldwide because after she had broken her engagement to Lord Eliot, the young heir to the earldom of St. Germanes, he committed suicide.

“It is seldom that an American girl—a true American girl—in marrying a foreign nobleman ever finds happiness…”

On September 5, 1909, the New York Herald wrote, “Miss Christy now is living in a handsome suite of apartments at Rossleigh court, No. 1 West Eight-fifth street. She was interviewed there and gave the whole story of the wooing of Lord Eliot.” Estelle clarified that the engagement had not been called off because the parents of Lord Eliot disapproved of her. “His mother seemed to take a great fancy to me, she said. The problem was that she was an all-American girl.

“It is seldom that an American girl—a true American girl—in marrying a foreign nobleman ever finds happiness. Their ways are not our ways, and girls who have been reared on this side of the water cannot adapt themselves to the life that is led in Europe.” She noted as well, “At no time did he show that he took the breaking of our engagement so seriously as to cause him to brood over it.”

The affluence of the building’s residents was reflected in 46 of the 59 resident families being listed in the 1911 Dau’s Blue Book of New York Society.

That year Ellen Glasgow took an apartment and would remain through 1916. Born Ellen Anderson Gholson Glasgow in Virginia in 1873, she had begun writing at the age of 24. Unusual for a women author at the time, her writings dealt with real women’s issues. The heroine of her first novel, The Descendant, avoided marriage in favor of passion. Her Phases of an Inferior Planet dealt with the breakdown of a marriage and the “spirituality of female friendship.” Glasgow’s topics also included class struggles, poverty, and psychological conflicts. By the time she moved into Rossleigh Court, she was an ardent suffragist, as well.

A most colorful couple living here at the time were Gustave E. Fauser, a decorative artist, and his wife Margaret. New Yorkers first realized there was trouble in the household when Fauser had Margaret arrested and committed to Dr. Carlos F. McDonald’s sanitarium for the insane on May 19, 1911. According to Fauser, “she had repeatedly threatened to kill him.”

After ten days of observation, Dr. George M. Parker deemed her sane. He said in court, “she is of a highly excitable and nervous temperament, but by no means irrational…She is perfectly sane.” Margaret admitted to threatening him because of “his actions toward her eighteen-year-old daughter, who was then living with them.” (Oddly enough, by today’s perspective, no one seemed to have been interested in the claims that Fauser had molested his teen-aged step-daughter.)

Each of the Fausers had long histories. Margaret was 35 years old and born in Kentucky. Her daughter was the product of her first marriage when she was 17 years old. She divorced that husband, and then three more. Her attorney explained, “One of them shot at her one time on the street while her divorce was still pending, but her companion interposed his body and was instantly killed. She received three bullets.”

Fauser had also been repeatedly married. Margaret was his third wife. As the judge released her, he directed Fauser to stay away. “You always want to be talking. Your wife here is also high strung and when two locomotives meet at high speed there is sure to be a collision.”

The collision came soon enough. On July 20 Margaret received an order to vacate her apartments “in the fashionable Rossleigh Court,” as worded by The Recorder. The article said, “She sent word to the superintendent of the building that she would not be turned out into the streets on such short notice.” In fact, she had been expecting her husband to try to force her out and had already emptied the apartment. The article said, “Mrs. Fauser, in her rooms, had been holding the fort against possible intruders ever since Saturday, when, in spite of the efforts of her husband, she sent all the furniture to a storage warehouse.”

A battle played out there on July 21. Fauser and his attorney argued with Margaret’s attorney over who owned what. The public and ugly affair finally ended in court with their divorce. Fauser admitted abandoning Margaret, but still insisted “his wife is insane.” Justice Cohalan said, “If Mrs. Fauser is insane that is all the more reason why her husband should protect her [financially].” Fauser was ordered to pay $30 a week in alimony.

Several of the residents of Rossleigh Court were physicians. Among the earliest was Dr. Arthur Stein, an obstetrician, here in 1909. In the early 1910s Doctors S. Kleinberg, William Ahlstrom, Theron Wendell, and Morris Grossman were here. In 1915 Dr. Ahlstrom went to the battlefront in Alsace, France with the Red Cross American Ambulance Corps for several months.

Living together here in 1919 were bachelors Solomon Shuldinger and Gerome S. Dumont, described by The Sun as “two young men who started in the importing and exporting business in a small way in Jersey City in 1914, and progressed rapidly until their company occupied the building at 139 Maiden Lane.” The empire they had built began to crack when, on August 7, 1919, they appeared in Federal District Court indicted with conspiracy to defraud the United States. The charges accused them of having embezzled $100,000 from the Government and Central Railroad of New Jersey through fraud.

When their case came to trial in March 1920, the pair had discreetly moved to separate apartments. Dumont retained the Rossleigh Court accommodations, and Shuldiner now lived on West 75th Street. Both pleaded guilty to the charges. Their sentences were surprisingly light—five days in the Tombs downtown.

Fauser admitted abandoning Margaret, but still insisted “his wife is insane.”

A colorful resident was James Churchill, known as Handsome Jim, who lived here with his wife, Anna. Churchill had started out with a fourth-grade education as a beat cop in 1883. He was fired from the force after 20 years “for knowing too much,” according to The New York Sun, and in 1903 made a striking career change by opening Churchill’s Restaurant on Broadway at 39th Street. The New York Sun said, “he made a fortune in the restaurant business after his dismissal from the Police Department.” Indeed, in 1909 he sold his restaurant to build the 1,200-seat Churchill’s Restaurant on 49th Street. When Prohibition was enacted, Churchill retired.

He had been offered the position of Prohibition Administrator by President Warren G. Harding, but he turned it down. He later recounted having said, “Mr. Harding, I sold liquor for about fifteen years before prohibition went into effect. What would you think of a man who would turn tail on his friends who are now selling liquor and try to stamp them out? I must refuse the appointment.”

Churchill died on January 19, 1930. His casket was taken from the Rossleigh Court, and the funeral party marched to the Roman Catholic Church of the Holy Trinity at 211 West 82nd Street. Among the mourners were old-time members of the police department, show business names like Marie Dressler (The Sun said, “Irving Berlin couldn’t attend, but he sent a huge pink floral piece), and well-known restauranteurs like William Healy and John J. Cavanagh.

The building continued to see a substantial number of physicians rent apartments. In the 1930s Drs. George H. Sherwood, Sigmund Pollitzer, and Henry W. Mooney lived here. And by the late 1950s, physician and amateur singer Leopold Glushak had an apartment. Born in Werro, Estonia, he was a plastic surgeon and a specialist in diseases of the eye, ear, and throat. He became a member of the staff of the Hospital for Joint Diseases starting around 1930.

A trained tenor, during World War I, while he was studying at the Army Medical School in Washington, he “went to the rescue of the Washington Opera Company, taking the Canio role in ‘Pagliacci’ when a regular performer could not make it,” according to The New York Times. So successful was his performance that he was brought back as Fatist for five more performances before he left to study in Europe. In 1938 Dr. Glushak helped found the Doctors Orchestral Society. He retired in 1957 and died in his apartment here on March 24, 1964.

At some point, the management or residents decided to change the address from 1 West 85th Street to the more impressive sounding 251 Central Park West. But little else has changed, at least from the exterior, over the building’s 115-year history.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

RETURN TO CENTRAL PARK WEST

BUILDING DATABASE

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business currently at 251 Central Park West:

Meet Dr. Brad Schaeffer!