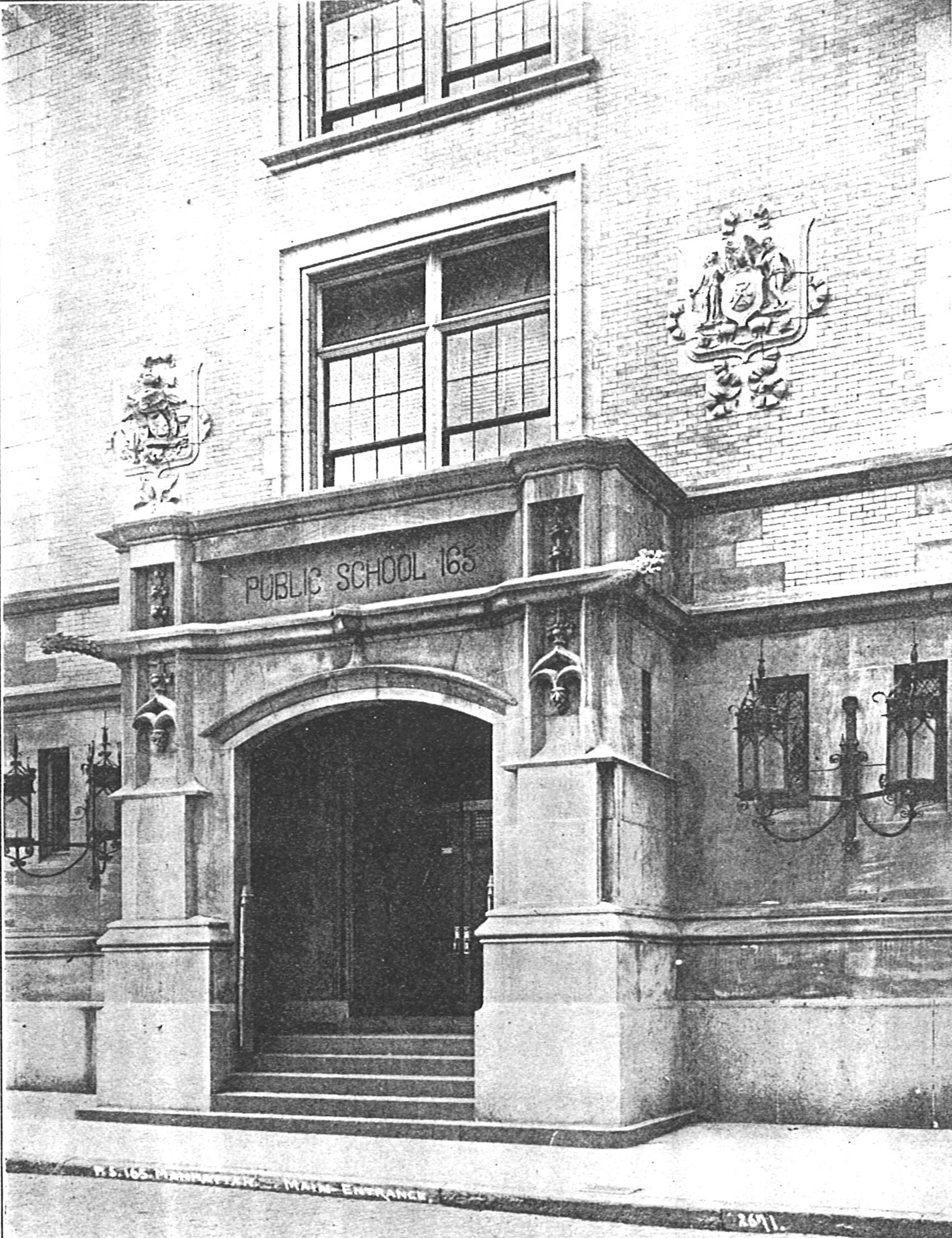

P.S. 165, 234 West 109th Street

by Tom Miller

Listed on the Board of Education’s list of “New schools to be opened during the year 1900,” was “New Public School 165, One Hundred and Eighth and One Hundred and Ninth streets, Amsterdam avenue, 47 class-rooms.” The entry noted that the building could accommodate 2,110 “sittings.”

Public School 165 and the other 13 school buildings on the Board of Education’s list had been designed by Charles B. J. Snyder, who took the position of Superintendent of School Buildings on July 1, 1891. Before he would retire in 1923, he would design more than 700 school buildings within the five boroughs. He changed the way architects would design school buildings going forward—with a focus on natural light, ventilation, and fire safety.

Public School 165 exemplified Snyder’s innovations. It was his first building to design on the H configuration, later a Snyder hallmark. It allowed the Board of Education to place the school on a less-expensive mid-block parcel rather than a corner plot yet still afford light and ventilation to all classrooms. It also had the advantage of being removed from the noisy avenues. Perhaps more obvious to the passerby, however, was Snyder’s French Renaissance design. Like a palace of King Francis I, the six-story structure featured elaborate dormers that sprouted spiky pinnacles. From the center of the red-tiled roof rose a cooper fleche. Construction began in May 1897 and was completed in time for the school season of 1900.

School buildings doubled as community centers. Like all others, Public School 165 hosted public lectures in the auditorium. On April 4, 1906, for instance, Dr. William MacDonald spoke on “The War in the Middle States,” and on October 23, 1909, the Record & Guide reported that Dr. James Walter Crook, professor of economics at Amherst College would be delivering a series of eight public lectures “on economics that, besides being exceptionally interesting, are of a nature calculated to be instructive and valuable to property owners.”

School buildings doubled as community centers.

Decades earlier, in 1857, engineer George E. Waring, Jr. was appointed the agricultural and drainage engineer for the construction of Central Park. In 1895, with street conditions intolerable—with millions of pounds of horse manure, garbage piles, and even horse carcasses in the streets—Warning established the Street Cleaning Department. In 1906, he made a brash proposal—the “enlisting [of] the boys and girls of the city as aids to the Street Cleaning Department,” as reported by the New-York Tribune. Perhaps surprisingly, a group of P.S. 165 boys responded by telling principal David E. Gaddis that they wanted to form “a Waring League.”

On February 10, 1907, the New-York Tribune quoted Gaddis, who explained, “It came up just at promotion time, and I told them they would have to do it all—I was too busy. They took hold of it with great enthusiasm, and before long all the nine hundred boys [in the school] will be organized.”

Less positive press came about in September 1918. Miss Ida A. Everett, who was 64 years old, obtained a license as a substitute teacher and was assigned to Public School 165. But then, Superintendent Ettinger discovered that 22 years earlier, Everett had written a love letter to another teacher, who was married. That teacher’s wife initially complained but later withdrew her action. It was too late for Ida Everett, who was fired and her teaching license revoked.

Although Everett had finally been able to regain her license, it seemed to be for nothing. The New-York Tribune, on December 11, 1919, said, “Miss Everett in her application said she must earn her own living.” The principal of Public School 165 wrote to the Board of Education on her behalf. Whatever the letter contained moved the Board. On December 10, the members approved of her reinstatement.

In 1936, while retaining the P.S. 165 designation, the building was named the Robert E. Simon School.

The public continued to use the auditorium for meetings and events, which naturally changed with the social and political environment. On December 3, 1968, for instance, an announcement in the Columbia Daily Spectator was titled, “Help Build A Community-Student Alliance To Stop Columbia’s Urban Removal Plan. Join The New West Side Community Council.” The group was protesting the Columbia-backed Morningside Renewal project. The meeting was scheduled for December 5 in the P.S. 165 auditorium.

In the summer of 1979, School Chancellor Frank J. Macchiarola announced that two Upper West Side schools would be closing—Public Schools 165 and 179. Clinton Howze, Jr., Superintendent of District 3, said the families “range from poor to affluence” and “80 percent of the pupils are Hispanic.” On June 7, 1979, The New York Times reported, “parents have set up picket lines outside [of both schools] to demand that the schools be kept open.”

Public School 165 survived the tumult, but now shared the building with other entities, like the Board’s Support Team and the Committee of the Handicapped, which “evaluates and places handicapped children, here in 1981.

When Ruth Swinney took the position of principal of Public School 165 in September 1993, she faced a formidable challenge. The New York Times reported, “crack dealers badgered teachers going to work in the morning and school children in the playground during the day…One Monday morning, school workers collected more than 100 crack vials around the school.” Swinney worked with the local precinct on eliminating that problem, but she also had internal difficulties.

“crack dealers badgered teachers going to work in the morning and school children in the playground during the day…One Monday morning, school workers collected more than 100 crack vials around the school.”

On July 20, 1995, The New York Times recalled,

Teachers came to school burned out and bitter. Students and parents ducked for cover during shootouts on the school’s street, drug-infested West 109th Street. Roaches climbed children’s legs in the lunchroom. An asbestos cleanup crew stole half the computers in the sagging, 1890’s building. And a parade of state and city investigators wrote incessant reports on the school’s failures.

Then, after years of the school’s substandard performance, in July 1995, Swinney’s work became evident. Public School 165 was removed from the state’s list of 68 failing elementary and middle schools in the city. The district superintendent pointed to changes put in place within the past two years. They included a school-based planning council of parents, teachers, and administrators to help improve students’ performance; staff developers that trained teachers on guidelines; and the use of more English in the classrooms, “creating a dual language, rather than bilingual program.”

By 1997, Crossroads School operated within the building. With 145 students and nine teachers, New York Magazine said on May 19 that year, “It’s not what a school would publish in its brochure, but over five years Crossroads has built a whispered reputation for making genuine students out of career school-phobes.”

And in September 2001, the fourth floor of the building became home to Mott Hall II, a selective middle school. The 2008 New York City’s Best Public Middle Schools notes that Mott Hall II prepares “kids from upper Manhattan for the city’s best high schools.”

Charles B. J. Snyder’s groundbreaking design for Public School 165 remains a dignified presence in the neighborhood–a slice of the Loire Valley on the Upper West Side.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com