230 Central Park West – The Hotel Bolivar

by Tom Miller

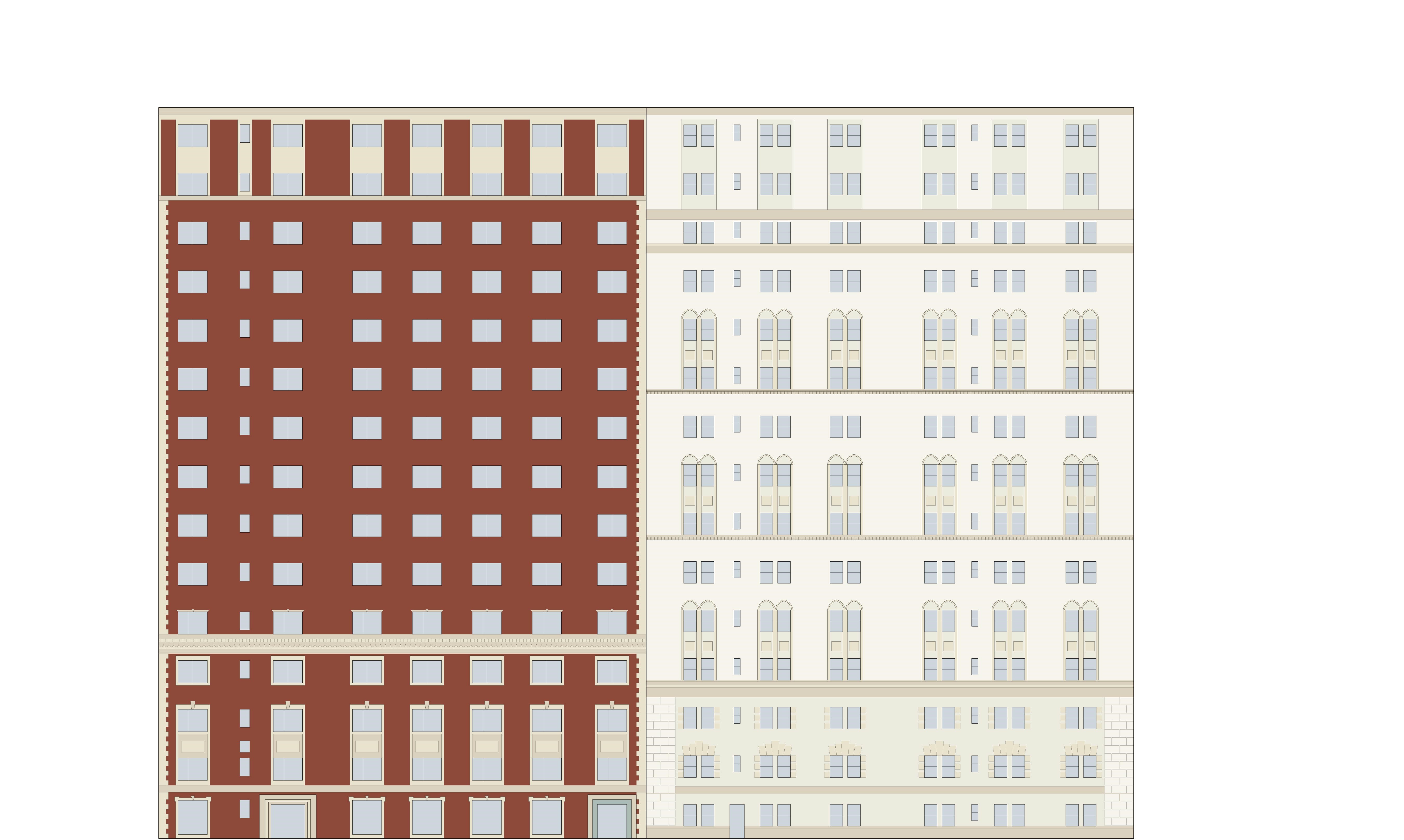

The 230 Central Park West Corp. was formed in 1926 specifically to erect a 15-story residential hotel on the southwest corner of West 83rd Street and Central Park West. Designed by Nathan Korn, the Hotel Bolivar was completed the following year. Korn faced his neo-Georgian style structure in Flemish bond brick and trimmed it in limestone. Eighteen-century motifs like splayed keystones and panels embellished with neo-Classical swags carried out the Georgian design.

An advertisement for the Hotel Bolivar called it “a homelike residential hotel.” Tenants could choose from “1, 2, 3, or more rooms with or without furniture.” Because it was a residential hotel, unlike an apartment, the suites included a “serving pantry” rather than a kitchen. Residents could take their meals in the “unusual restaurant,” as described by the ad. Larger apartments had wood-burning fireplaces. An advertisement boasted, “Private bath with every modern convenience including glass-enclosed cabinet shower.” Rents began at $840 per year—or about $1,500 a month in 2024 money.

Among the early residents were Dr. Louis C. Loewenstein and his wife, the former Margarete Lewy. Born in Mora, New Mexico, Loewenstein studied engineering both in America and Germany. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Berlin in 1900. His resume was more than impressive. Loewenstein had been the designing engineer for the Cramp Shipyard and the New York Shipbuilding Company, was a consulting engineer to the General Electric Company and a consulting expert to the Department of Justice. An inventor, he held more than 200 patents. Additionally, he was president of the National Power Machinery Corporation and the Electrolier Fire Extinguisher Company and was a member of the editorial staff of the Mechanical Engineer’s Handbook.

The Kriezvogels had little choice, since all three men had weapons drawn.

The Hotel Bolivar Restaurant’s American cuisine was touted in a 1940 advertisement as “excellent food served in a pleasant, homelike atmosphere.” Lunch prices started at 65 cents, and dinners at $1.00.

To escape the frigid New York weather, N. F. Kriezvogel and his wife went to Miami Beach, Florida in February 1941. At 3:30 on the morning of February 15, the couple left the Royal Palm nightclub where they had spent three hours gambling. Kriezvogel told police, according to The Evening Recorder of Amsterdam, New York, that as they walked up the driveway to the Shelbourne Hotel, “three men drove into the driveway alongside him and his wife and forced them to step among the automobiles parked at the side.” The Kriezvogels had little choice, since all three men had weapons drawn. The bandits made off with $38,575 in jewelry and $120 in cash—a haul equal to $800,000 today.

Otto and Jessie Strassburg were residents at the time. Born in Mannheim, Germany, in 1877, Strassburger had been an employee of the newly-formed private Hamburg bank Ludwig Tillman (named after its founder) in 1894. The members dispersed as the Nazi Party came to power, Otto and Jessie moving first to Italy. After a brief stop in Switzerland, they fled to the United States via Portugal in 1940. On February 19, 1943, Jessie Strassburg placed a touching notice in the German language newspaper Aufbau. Translated, it read, “On February 12, 1943, he suddenly succumbed within a heartbeat of reaching the age of 66, my dearly beloved husband, Otto Strassburger.”

George Herrick was arrested in his apartment on March 15, 1942. The New York Sun explained, “George Herrick, whose lavishly appointed gambling salons have long catered to the white tie trade on the fashionable East Side of Manhattan and on Long Island, is having his little troubles with the Treasury Department’s Internal Revenue Bureau.” The “little trouble” was that he had failed to file tax returns for the years 1935 through 1939. His excuse was naivety, saying “he was unaware gambling proceeds were taxable.” The IRS was not sympathetic, and his trial was set for March 30.

U.S. Army Captain Morton S. Bryer married Gladys Law in June 1944. Soon after they moved into the Hotel Bolivar, Captain Bryer was deployed with the Army Medical Corps to Europe, leaving his bride alone. After a few months, Bryer’s father and brother-in-law were not certain that Gladys was, in fact, alone. They hired two private detectives, and on June 16, 1945, stormed into a room on the 25th floor of the Hotel Lexington “where they said they found the wife with a man, not her husband,” according to the Freeport New York Daily Review. On September 29, 1945, the newspaper said that through their efforts, “the marital bonds of Morton S. Bryer…today had been unloosed from Gladys Law Bryer.”

The “little trouble” was that he had failed to file tax returns for the years 1935 through 1939.

In the last quarter of the 20th century, when the building became cooperative apartments, the “Hotel” was dropped from its name. Residents of The Bolivar were most likely shocked to read in The New York Times on December 1, 1977, that a neighbor, 32-year-old Paul Abrams, had been arrested in his apartment. The article began, “A major ‘call boy’ operation in New York City has been smashed and the files containing the names of hundreds of male prostitutes and prospective customers have been seized, vice squad detectives said yesterday.” Abrams, who listed his profession as a photographer, called his operation “Dial a Model.” He was described by Sgt. Philip Tambasco of the public morals squad, “one of the biggest call boy procurers” in New York.

In 1990, the same year his popular television sitcom began, stand-up comedian Jerry Steinfeld purchased a two-bedroom apartment here. Nine years later, he married author Jessica Sklar. The couple remained in The Bolivar apartment while work was being done on their new apartment in Beresford, a block away. After moving into that apartment, they maintained The Bolivar space for out-of-town guests. The Seinfeld’s finally sold it in 2006.

Despite unsympathetic replacement fenestration and distracting air conditioners that either protrude from windows or have been gouged into the masonry, The Bolivar retains its dignified, 18th-century-inspired presence after nearly a century.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

RETURN TO CENTRAL PARK WEST

BUILDING DATABASE