Daly’s 63rd Street Theatre — 22-26 West 63rd Street

by Tom Miller

Real estate operator Benjamin Butler Davenport, who used his middle name professionally, formed the Davenport Stock Company in 1908–“a theatrical and musical organization,” according to The New York Times. The following year he acquired the property at 22 through 26 West 63rd Street from William Brennan and hired Thomas W. Lamb to design a theater on the site. Davenport was taking a risk with the fledgling architect. Born in Dundee, Scotland, Lamb had arrived in New York City at the age of 12 in 1883. This was likely just his second time designing a theater–his first coming from William Fox a few months earlier. As it turned out, Thomas W. Lamb would become one of America’s preeminent theater architects.

Lamb’s neo-Classical design featured arched entrances within the rusticated base. A full-width iron balcony fronted the second floor. Above, Lamb’s Roman temple design included shallow, triple-height pilasters that upheld an entablature and triangular pediment.

Construction began in April 1909. The 800-seat Davenport Theatre was scheduled to open in December that year. But, as autumn neared, Davenport’s finances dried up. On November 15, 1909, The New York Times reported, “Silence surrounds the unfinished little Butler Davenport Theatre, in West Sixty-third Street, which was to have opened this Winter as a home for untried dramas and a stock company headed by Mary Shaw.” The journalist described boarded up doorways and windows that “hide the debris-filled interior.”

Although various plans were proposed, the uncompleted shell sat for nearly four years. Then, on October 1, 1913, The New York Times reported that the People’s Pulpit Association and the International Bible Students’ Association, “religious organizations whose American headquarters is in the Brooklyn Tabernacle,” had purchased the property to become a temple by architect Erwin Rossbach. “The temple is completed practically, except for the placing of the 1,400 seats. It will be thrown open to the public late next month,” said the article.

The 800-seat Davenport Theatre was scheduled to open in December that year.

Rossbach modified Lamb’s interior plans, making it less “theater” and more “auditorium.” In addition to the worship services, said The Times, “Biblical plays in moving pictures will be shown, and these will be taken especially for the Pulpit Association. Motion pictures and magic lantern views will also be shown to illustrate the talks of the lecturers.”

On December 1, 1913, the Watchtower reported that “Dedication Day” of the New York Temple would be Sunday, December 7. On that day, 850 people attended the all-day ceremony. The first motion picture viewing was the Photo-Drama of Creation on January 11, 1914. The Temple’s pastor, Charles T. Russell, reportedly filled the building on Sundays with as much as 1,500 worshipers.

The Temple was the venue of Reverend Russell’s funeral service on November 5, 1916. On December 15, 1917, the Watchtower announced that the building had been sold. The purchaser, Maurice Runkle, intended to convert the building into a theater. Instead, he lost it foreclosure to William F. Clare for $200,000 on June 14, 1918. Clare brought back Thomas W. Lamb to remodel the building at a cost of $75,000 (just over $1.3 million in 2025). The renovated theater would hold 1,800 patrons.

The New York Times reported on August 20, 1920, “The Davenport Theatre Building…has been subleased to the Sixty-third Street Corporation,” headed by John Cort. Innovative and bold, Cort immediately brought avant-garde productions to what was called the Sixty-Third Street Musical Hall.

On May 22, 1921, for instance, the musical Shuffle Along opened at the 63rd Street Music Hall. The New York Times wrote that it had, “the distinction of being written, composed and played entirely by negroes,” adding that it had “a swinging and infectious score by one Eubie Blake.” Blake had collaborated with Noble Sissle on the libretto. Among the tunes to come from Shuffle Along was the highly popular, “I’m Just Wild About Harry.” The ground-breaking musical would run for two years. In March 1923, Cort introduced the Black composer duo Rogers and Roberts’s Go-Go, and in November, the team’s Sharlee opened.

By 1927, Cort had renamed the venue Daly’s Sixty-Third Street Theatre. That spring, Earl Carroll’s White Cargo was playing here when John Cort heard about a new show that had sailors from the navy station in New London snaking around the block. He traveled there to see it, then brought Mae West’s Sex to the Sixty-Third Street Music Hall. He had to pay off the cast of White Cargo to end its run early.

On April 27, 1926, The New York Times opened its critique of Sex saying, “A crude, inept play, cheaply produced and poorly acted—that, in substance, is ‘Sex,’ which came last night to Daly’s Sixty-third Street Theatre.” Despite the panned reviews—or perhaps because of them—Sex was a smash. Life magazine opined on May 20, “’Sex,’ one of the most banal of plays, was a whacking hit, solely because the papers had said that it was ‘vulgar’ and ‘bold’ and because some one had the genius to think of its name.” Sex ran 385 performances. In his The Complete Films of Mae West, Jon Tuska writes, “Had it not been raided and had Mae not been jailed, it probably would have run longer.” (John Cort was also arrested, but the charges were later dismissed.)

The building was sold in 1929, triggering a rapid-fire change of names.

Cort continued to stage edgy productions here. On July 2, 1927, The New York Times reported, “’Africana,’ another negro musical entertainment, is scheduled to open at Daly’s Sixty-third Street Theatre.” And on February 28, 1928, the newspaper announced, “A canvas banner stretched across West Sixty-third Street last night welcomed Miller and Lyles back to Daly’s Theatre, where they first came into success in ‘Shuffle Along.’” The entertainers were among the cast of Keep Schufflin’.

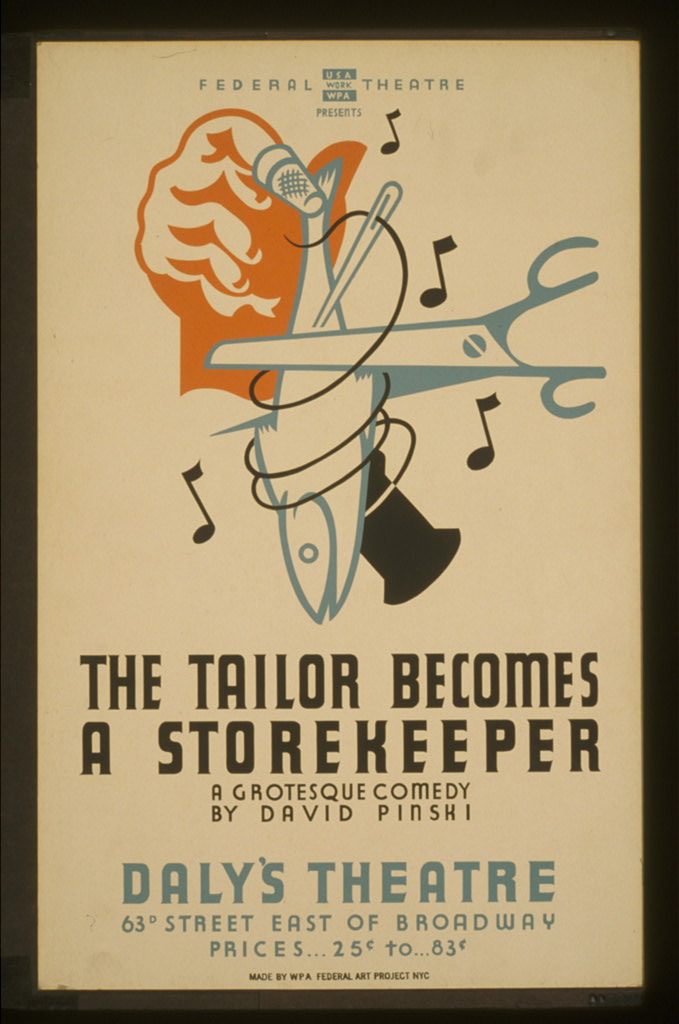

The building was sold in 1929, triggering a rapid-fire change of names. On April 4, 1932, The New York Times reported, “Daly’s Sixty-third Street Theatre, which has also been known recently as the Recital Theatre, will hereafter be the Park Lane Theatre.” That phase was short-lived, as well. By 1936, it was once again Daly’s Theatre. That year, in March, the Work Progress Administration’s Experimental Theatre took over the space (while keeping the name this time).

Unlike most live theaters erected in the first decades of the century, Daly’s Sixty-third Street Theatre was never converted to a motion picture venue. The last production closed in September 1941, and the building sat dark for seventeen years. In 1957, it fell victim to the massive urban renewal Lincoln Square project.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com