211 Central Park West – The Beresford

by Tom Miller

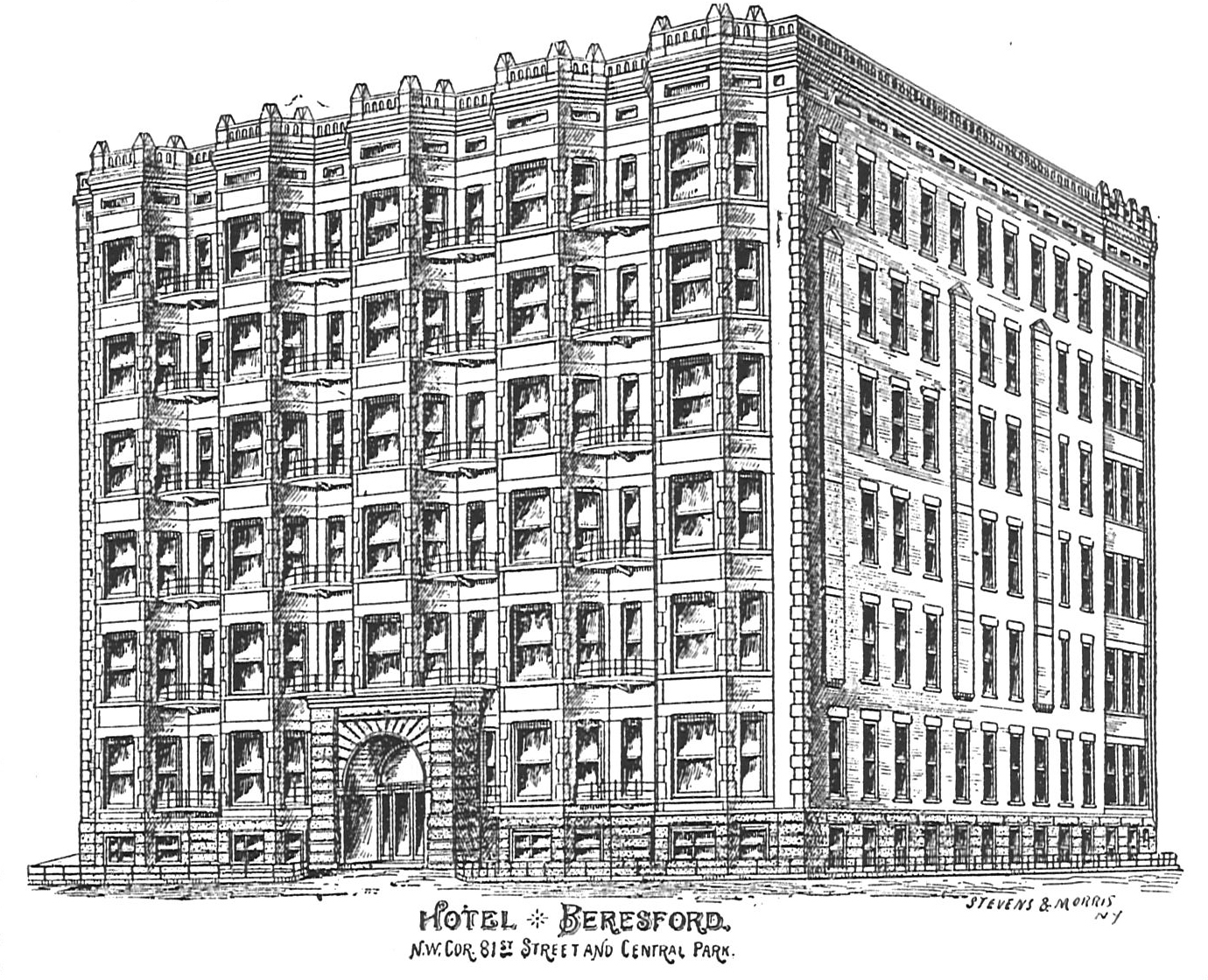

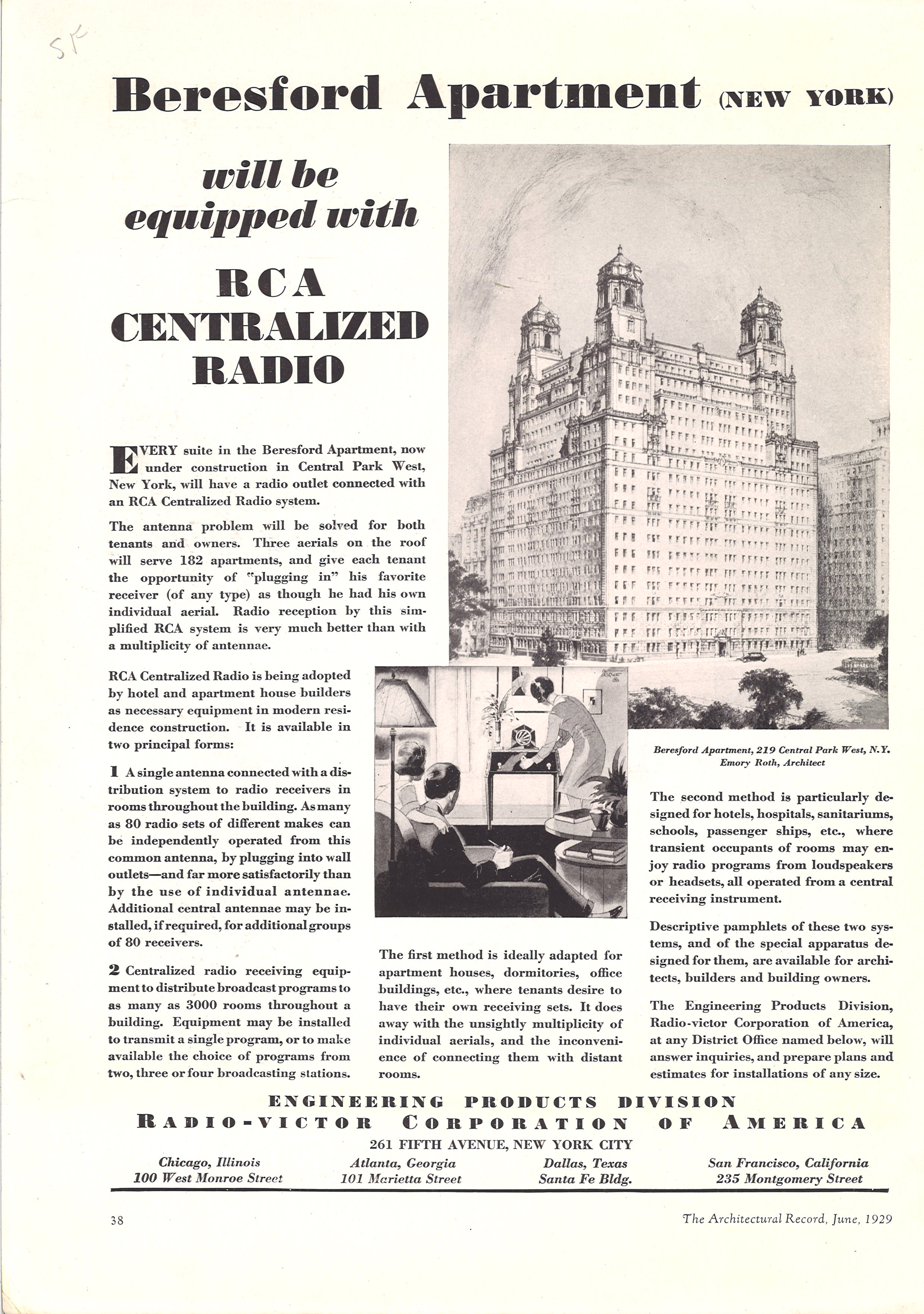

In 1928, four decades after it opened, the once-lavish Hotel Beresford was out of date. In August, the H. R. H. Construction Co. demolished the Victorian landmark and began construction on a modern, upscale replacement. Engulfing the blockfront from West 81st to 82nd Streets, the eminent apartment building architect Emery Roth designed the structure.

The 23-floor structure was completed on September 13, 1929. Roth had produced an imposing structure based on the Late Italian Renaissance, with added Baroque elements. Its great, yellow brick mass rose above a limestone base to three towers that perfectly disguised the water tanks–normally an eyesore.

The extravagant lifestyles of the wealthy during the 1920s were reflected in the floorplans. The 182 apartments–some of which, with 12 rooms, were the size of a townhouse–contained servants’ rooms, cedar-lined storage closets, sun porches, dressing rooms, and service hallways separated from the main living quarters. The New York Times said, “Living rooms average 20 by 30 feet. Each apartment has a separate service elevator and service foyer.”

Writing in The New Yorker on November 23, 1929, Marcia Clarke Davenport was relieved that one could still find “really large rooms, really high ceilings; and you can pay–very, very well for them.”

Six weeks after The Beresford opened, the Stock Market crashed. The Great Depression would eventually have devastating consequences for the building’s owners, but its monied residents, on the other hand, seem to have been little affected.

The initial tenants were widely varied. Their wide range of professions was reflected in three of the initial families: Maurice S. Benjamin; David Israel and his wife, the former Lilian Ratner; and Jack Donahue, his wife, Alice Stewart, and their three daughters. Benjamin was a partner in the stock brokerage firm of Benjamin, Hill & Co.; Israel was the founder and president of David’s Specialty Shops with ten stores around the country; and Donahue was a highly popular dancer and entertainer.

Jack Donahue once said that in the neighborhood of Boston where he grew up, “the boys didn’t worry about what they were going to do when they grew up–you were going to be either a dancer or a fighter.” He chose dancing. The New York Sun later said his “dancing feet brought him fame and fortune as a favorite of the musical comedy stage.”

He debuted in New York in 1912 in The Woman Haters, performing a tap dance with a whisk broom. By the 1920s, he was a Broadway star. When he and his family moved into The Beresford in 1929, he was starring in Sons o’ Guns. The show went on the road in the fall of 1930.

“the boys didn’t worry about what they were going to do when they grew up–you were going to be either a dancer or a fighter.”

During that tour, Donahue was afflicted with a sinus infection. On October 1, 1930, The New York Sun reported, “Overwork, however, coupled with a weakened condition, caused by other ailments, made him collapse last Thursday in Cincinnati. He was forced to leave the show and come to New York for treatment.” But back at The Beresford, he refused medical attention.

“I’ll be all right, after a rest,” he told his family and friends.

He had tragically underestimated his condition. At 5:45 on the morning of October 1, he died at the age of 38. The New York Sun said, “The end came suddenly. The immediate cause of death was heart disease and a chronic kidney ailment, it was announced.”

Living in The Beresford at the same time were organists Jesse Crawford and his wife, the former Helen Anderson. The couple played the twin organ console at the Paramount Theater. On February 3, 1933, the Times-Union wrote, “The private life of Mr. and Mrs. Jesse Crawford chime together as smoothly as the melodious notes of music they evoke, in concert, from the depths of their gigantic twin organ.” Living with them in their Beresford apartment were their daughter, Jessie, and their wire-haired terrier, Honey. Helen was, as well, a songwriter whose works include So Blue and The Moonlight Reminds Me of You.

A somewhat colorful tenant was Frank J. Moore, called the “dean of clubhouse commissioners.” He and his wife, the former Anna Moore, had a grown daughter, Alice. The millionaire had started out as a jockey and stable agent in the 1880s. He eventually “handled betting transactions for many of the country’s most prominent turf followers,” according to The New York Times.

A disturbing incident occurred in 1932. With the investigation into the kidnapping of the Charles Lindbergh baby still making headlines, Louis Marx and his wife began receiving letters threatening to kidnap their two little children. The writer initially demanded $20,000, then raised the price to $50,000–just under $100,000 in today’s money.

The investigation ended with a shocking discovery. The letters had been written by Marion Harris, the family’s live-in English nursemaid. She confessed to the scheme, insisting that she worked alone. Surprisingly, Louis Marx appeared at her hearing, not as her accuser, but “as a friend of the defendant,” according to The Sun on March 27, 1933. “This is not a vicious woman,” he told the judge, “she loved my children and gave them excellent care.”

The arresting officer was not so sympathetic. The Sun remarked that his “long experience has tended to make him a little hard boiled.” He countered that while she was demanding what amounted to ransom, “she gave each of them a black pill which had the effect of running up their temperature.”

Marion Harris became hysterical, sobbing, “I was forced by these policemen to sign that confession. I should never have done it.”

Hyman H. Butler and his wife, the former Rachel Ellenbogen, moved into The Beresford when it first opened. He was the founder of a nationwide chain of 23 clothing stores. They maintained a country home, Pinehurst Farms, at Crystal Lake, at Averill Park, New York, where Butler bred Hackney thoroughbreds.

Rachel Butler died following a long illness on December 14, 1954. In her memory, in July 1956 Butler donated 62 acres of land to the Averill Park Central School District as the site of a new school building. Hyman Butler would remain in the apartment until his own death on May 13, 1970.

The Beresford was converted to co-ops in 1962, by which time it was filling with celebrated names. Among them were internationally renowned concert violinist Isaac Stern and his wife, Vera. The couple was greatly upset when Jacob Goldfarb purchased the apartment directly above them in 1962 and began renovations.

On June 14, 1963, the Buffalo Courier-Express reported, “A concert artist must be undisturbed in his early morning sleep and rest. That’s what violinist Isaac Stern contended Thursday in asking a State Supreme Court injunction against what he called ‘unbearably loud noises'” from the Goldfarb apartment. The Sterns were asking $50,000 for damages suffered in the months-long renovations.

Television personality Allen Funt was in court the following year. The creator and host of “Candid Camera” sued the co-op board when it refused his request to glass-in his terrace. His suit, filed in September 1964, sought $600,000 in damages, and said the refusal was “capricious, arbitrary, unreasonable.”

Among the Funts’ neighbors was the family of Seymour and Eda Mann. Mann owned a gift and home accessories firm notable for its mass production of porcelain dolls designed by Eda, who also designed textiles. Their daughter, Erica, graduated from Barnard College in 1963 with a master’s degree in English Literature.

The Mann apartment was the scene of Erica’s wedding to Army Captain Allan Jong on February 27, 1966. Erica Jong would achieve fame as a novelist, poet, and satirist, especially known for her 1973 novel Fear of Flying.

Another celebrated tenant was motion picture actor Rock Hudson, who lived in the penthouse apartment on the building’s southeast corner. He died at the age of 59 in October 1985. The apartment was purchased in 1998 by Nicholas J. Clay, who told a reporter from The New York Times, “We basically ended up having to completely redo the whole of the inside of the apartment” to make it “more of a family apartment.” The Clays sold it to actress Glenn Close and her partner, biotechnology entrepreneur David E. Shaw, in 2005 for just under $6 million.

“A concert artist must be undisturbed in his early morning sleep and rest. That’s what violinist Isaac Stern contended Thursday in asking a State Supreme Court injunction against what he called ‘unbearably loud noises'”

In the meantime, comedian Jerry Seinfeld paid $4.35 for the Isaac Stern apartment in February 1998. At the time, other well-known residents included operatic soprano Beverly Sills, actor Tony Randall, author Helen Gurley Brown, and film director Sidney Lumet. In reporting that Seinfeld still had to pass the co-op board’s approval, The New York Times journalist James Barron quoted a resident who said, “No one’s particularly worried–the building already has a celebrity quotient.” But Barron wondered, “But Kramer will be able to wander in?”

Beverly Sills had moved into The Beresford in the 1930’s and shared it for decades with her daughter, Meredith Holden Greenough. Among her neighbors were author and composer Mary Rodgers, daughter of Richard Rodgers, and her husband Henry Guetell, a theater producer and film executive. Robin Finn of The New York Times said their apartment “often resonated with song and sound from the Steinway grand piano tucked into the front corner of the living room.” Among the “impromptu performers” at their gatherings, according to Finn were “Stephen Sondheim, Harold Prince, Julie Andrews, Itzhak Perlman, Bernadette Peters, Diana Ross and Lang Lang. Even Woody Allen attended a fete or two.” Finn added that Beverly Sills “had a standing invitation.”

For decades, apartment 19E, a terrace duplex, was home to actress Phyllis Newman and her husband, Adolph Green. They reared their two children, Amanda (who went on to become a Broadway songwriter and performer) and Adam (later a theater critic) here. Green died in 2002 at the age of 87, followed by Newman in September 2019 at 86.

Two months later, the children put the apartment on the market for $24 million. In reporting the move, The New York Times reporter Vivian Marino noted that the couple had hosted glittering parties in the duplex. “Lauren Bacall and Glenn Close (a neighbor) were among their guests, as were Groucho Marx and Milton Berle, and the musical luminaries Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim, Jule Styne, and Isaac Stern (their next-door neighbor).”

In 1982, Tony Award-winning actor Roger Rees and his playwright husband Eric Elice purchased “a four-room aerie” in The Beresford. Then, in 2005, they bought the two-bedroom apartment directly above and created a duplex.

Other celebrity residents over the years included former tennis great John McEnroe, singer-songwriter Patty Smyth, and actress-singer Diana Ross.

Despite the passage of time, apartment buildings along Central Park West never lose their panache. A five-bedroom “house-like residence,” as worded by a realtor, in The Beresford recently appeared on the market for $40 million.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

RETURN TO CENTRAL PARK WEST

Landmarks Timeline

BUILDING DATABASE

Designation Report

Explore Even More!

Read more about this landmark from our partners at the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project!

NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project Site History