The New York Free Circulating Library aka the Ukrainian Academy of Arts & Sciences

by Tom Miller

Many New Yorkers could not afford the luxury of buying books in the 19th century, and prior to 1880, the few libraries that existed were not open to the public. But that year the New York Free Circulating Library was incorporated – an alternative to the Astor and Lenox Libraries (used mostly by researching scholars) and private libraries that charged membership fees. The response was so great that the sidewalks around the first library – a single room in a building on 13th Street near Fourth Avenue – were blocked. At closing time on one occasion, only two of the 500 books were left on the shelves.

At the time the Upper West Side was seeing the first real signs of development. But by 1898 it had become a vibrant suburb – one without a library. In 1917 the Bulletin of the New York Public Library recalled “Above 23d Street there was no free circulating library south of the Washington Heights Library, six miles and a half to the northward, except the small library on West 59th Street provided by the Riverside Association.”

Several churches offered their parish libraries to the New York Free Circulating Library, “but the trustees felt it best to wait until they could establish an independent branch.” Undaunted, Rev. Dr. Peters of St. Michael’s Church turned over its 1,000 volumes. Soon hundreds more books were donated and before long a makeshift library in rented rooms at 100th Street and Amsterdam Avenue was opened. The Upper West Side residents had made their point. The 1917 Bulletin noted “During the first full year of its existence the Branch circulated 105,410 volumes, the total number on its shelves being 6,253, which meant that each volume was taken out an average of 17 times during the year or once every three weeks, over twice the ratio of circulation for the whole system. Larger quarters were an absolute necessity.”

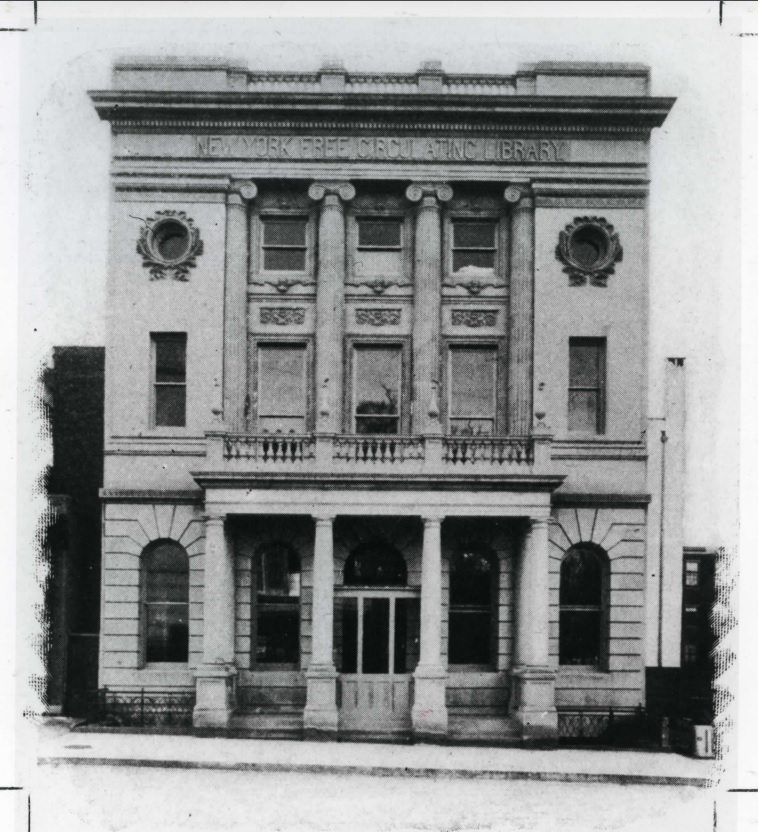

In February 1898 the plot at No. 206 West 100th Street was purchased for $12,900 – in the neighborhood of $380,000 today. Designed by esteemed architect James Brown Lord, the Bloomingdale Branch of the New York Free Circulating Library was completed that same year at a cost of $35,000. It opened on November 1. Lord had produced a striking Renaissance Revival building faced in limestone and trimmed with terra cotta. Its classic facade received a splash of Beaux-Arts in the form of leafy wreaths that encircled the oculi on the third floor. The projecting portico with its stone upper balustrade, the two-story Ionic columns on the upper floors, and the handsome parapet broken by another balustrade, produced a dignified presence. The architect was apparently pleased with his own work; for when he designed Andrew Carnegie’s Yorkville Library four years later he recycled several of the architectural elements.

Several churches offered their parish libraries to the New York Free Circulating Library, “but the trustees felt it best to wait until they could establish an independent branch.”

Three months after its opening, Literature magazine explained that windows at nearly sidewalk level and the absence of a grand flight of steps were purposeful. To young readers, it said, “a flight of steps leading up from the pavement to an invisible and unknown interior would not seem inviting, to say the least; but when they can look through a window and see other boys and girls reading or getting books from the librarian, that is a different matter. For one thing, they do not care to be outdone by their equals!”

The chairman of the Library Committee described the new building as “perfectly adapted” as a circulating library. And Literature said it “may serve as a model of its kind.” The first-floor stacks held 8,000 volumes. On the second floor was the Reading Room, where periodicals and reference books were housed. Said by Literature to have “quiet charm,” it had small tables for the use of researchers. As was the case with libraries nationwide, readers could use the facilities of the Bloomingdale Branch Library for free or take their choice of books home – as long as they had a library card. For one newly-transplanted New Yorker, that detail proved annoyingly difficult in 1906.

Using only his initials S. R. as identification as his signature, the disgruntled bookworm fired off a letter to the Editor of The New York Times on January 4. He had gone to the library that afternoon and filled out an application form for a library card. In the space labeled “Name of Reference,” he wrote in the name of his brother, “a member of a long-established and prominent business firm.” But the librarian tore it up and handed him a new form, “remarking that library rules forbade acceptance of so near a relative as reference.”

So the man asked if a more distant relative would do – one he described as “a woman whose name has appeared in the Directory twenty-five years, eighteen years from the same address, and who, as I well know, has often been given and accepted as reference in another library branch.” The librarian rejected this proposal, as well. “With scorn.” As the man scratched his head and pondered over his predicament, a young woman entered and exchanged familiar pleasantries with the librarian. She introduced a friend who wanted to get a library card. The women began filling out the blanks. Within earshot of the new Upper West Side resident, the librarian stopped the applicant. She said that if her friend would vouch for her, “you needn’t bother filling it out.” She handed over a library card.

In the meantime, S.R., who had not yet established close friends, was told to find “someone in business for himself and not a relative” as a reference. Fuming, he wrote his letter which ended by saying “I wish to inquire whether the above is the rule of the New York Public Library, and why the other woman was not compelled to comply with it.”

The Great Depression took its toll on City budgets and the operating hours of the Bloomingdale Branch were cut back. No doubt much to the joy of the neighborhood, the “limited schedules” were returned to normal in 1939. Throughout the decades, exhibitions and activities were regularly staged here. In September 1947 a South American exhibition in the Children’s Room opened, and the following month the Halloween picture-book hour was held for children between three and six years old. There were exhibitions for adults, as well. In 1948 a display of Frank Bowling’s photographs of Korea was staged; as was an exhibition of costumes and accessories of the 1890s.

On September 25, 1960, The New York Times announced that “The Bloomingdale Branch, 206 West 100th Street, which has been in service for sixty-two years will close its doors…”

On September 25, 1960, The New York Times announced that “The Bloomingdale Branch, 206 West 100th Street, which has been in service for sixty-two years will close its doors on Friday in preparation for a move to a building nearing completion at 150 West 10th Street.” The building was purchased by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences, a research organization established in 1950 by immigrants fleeing the Stalin regime. Their memories of the Communist government were still fresh when, in 1986, the Landmarks Preservation Commission proposed the building for designation.

The Academy’s attorney, Stephen J. Jarema reflected the group’s suspicions when he said flatly “Our people who were fortunate to escape from a police state are fully aware that once the government imposes a police power, no matter how innocent, it will not disappear, but grow in quest of more power. Forced obedience will replace freedom.”

But eventually, in September 1989, the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences acquiesced and James Brown Lord’s handsome structure was designated a landmark.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

206 West 100th Street

Landmarks Timeline

SUPPORT UKRAINE

Designation Report

Think Local First!

New York State offers THIS WEBPAGE (linked) for ways to help Ukraine.