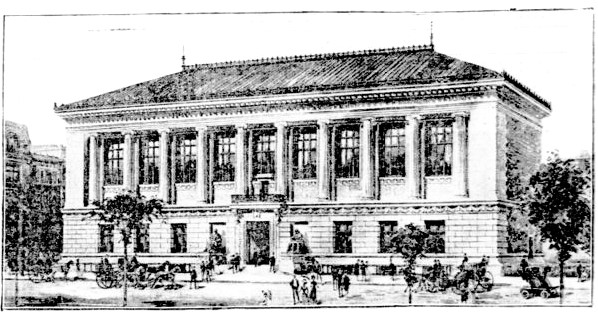

The New-York Historical Society Building, 170 Central Park West

by Tom Miller

Founded in 1804, the New-York Historical Society had moved several times before considering yet another location in 1902. On November 16 that year, the New-York Tribune reported,

The New-York Historical society’s one-hundredth anniversary is only two years in the future, and, in order that it may be fittingly celebrated, there is an earnest desire on the part of the members to begin next spring the new building designed to cover the block fronting in Central Park West, between West Seventy-sixth and Seventy-seventh sts., and to push the building to completion by 1904.

The article explained the current structure was “so crowded and inadequate that scarcely anything is properly shown.” The writer noted that much of the collection was “in storage until suitable quarters can be provided.”

The architects had already been commissioned and their renderings approved. York & Sawyer had designed a stately, Roman-inspired structure with a rusticated base and double-height columns at the upper section. Clad in gray granite it exuded an air of grandeur. Before the building was completed in 1908, the proposed hipped roof was replaced with a flat version.

In addition to its permanent collections, the New-York Historical Society staged temporary exhibitions. In August 1909, for instance, an exhibition of “objects of interest relating to Robert Fulton” collected by the Colonial Dames of America was staged. The society also presented free lectures to the public. On May 6, 1913, for instance, Albert Ulmann spoke on “Curiosities of New York History,” and six months later Thomas J. Burton gave “an illustrated lecture on ‘Old New York Churches.’”

The venerable organization received unwelcome news in February 1914. When Catherine Augusta de Peyster died on January 25, 1911, she left a bequest of $388,000 (about $12.3 million in 2023) to the society. The State of New York demanded taxes. In court, the New-York Historical Society claimed it was an educational institution and, therefore, exempt from taxes. The Sun reported:

The historical society showed that its library, which is open to the public, contains 119,838 volumes and 119,914 pamphlets, while there are 1,023 paintings in the New York Gallery of Fine Arts, the Bryan Gallery of Old Masters and in the Durr collection. The society has forty-eight volumes of Colonial and fifty-five volumes of Revolutionary manuscripts. In addition, free lectures are held during the year.

She was taken to the basement, where hundreds of artifacts were stacked in seeming disarray, including the French chair with its ripped and tattered upholstery.

The tactic failed. The Court of Appeals ruled that there was “a distinction between educational corporations and historical societies.” The New-York Historical Society was forced to pay $388,000 in taxes on the gift.

Many (if not most) of the Society’s long-term members came from old, distinguished New York families. Among them was Mrs. John King Van Rensselaer. She was made a life member in 1898 by her uncle, John Alsop King, who was its president at the time. Among the items in Mrs. Van Rensselaer’s home was a chair once owned by Marie Antoinette. It was one of a pair purchased by Gouverneur Morris. At some point, he gave one of them to a close friend and Mrs. Van Rensselaer’ grandfather, William Alexander Duer. The other was now in the society’s collection.

The Marie Antoinette chair was one of several historical pieces Mrs. Van Rensselaer hoped to present to the society. It occurred to her in 1917, however, that she did not recall seeing its mate on display on Central Park West. She went there and inquired about it. She was taken to the basement, where hundreds of artifacts were stacked in seeming disarray, including the French chair with its ripped and tattered upholstery. She also recognized in a corner the flagstaff of Fort Sumter which her father had presented to the New-York Historical Society in 1897.

The officers and executive committee met every three years, and as it turned out, 1917 was one such year. The New-York Tribune reported that for “more than a hundred and twelve years,” nothing more exciting than annual dues or yearly expenses had been on the agenda. But now, “like a bolt from the blue, Mrs. Van Rensselaer threw a hand grenade into the Family Dress Circle.” She said in part:

I hear on all sides that the society is dead…Instead of an imposing edifice filled with treasures from old New York, what do we find? Only a deformed monstrosity filled with curiosities, ill-arranged and badly assorted.

A special committee was formed to address her concerns. Mrs. Van Rensselaer countered to arguments of insufficient space (despite the relatively new structure), that the society needed organizing, cataloging, and special arranging of the collections.

The third quarter of the 20th century saw the exhibitions take on current issues. Mrs. John King Van Rennselaer’s open criticism drew the attention of Maria R. Audbon, the granddaughter of James Audubon. She wrote to the New-York Tribune, telling of how her grandmother, Audubon’s widow, sold more than 600 paintings to the Society in 1863. Two years later, in May 1865, her grandmother took her to a meeting of the New-York Historical Society “to ask why the drawings were not on exhibition.” Maria’s letter continued:

In those days young girls were not given to attending committee meetings, and I was greatly embarrassed and do not recall all I should, but I well remember that the assurance was given that when the society moved to larger quarters…a room or gallery was to be built exclusively for these drawings.

She noted, “As we left, Mr. [Frederick] De Peyster said to me: ‘That is how these big institutions escape their responsibilities and promises.’ Apparently, they have continued to do so.” At the time of her letter in February 1917, the 600 Audubon drawings were not on display. “Doubtless there are very many who would enjoy seeing these drawings, as my grandfather wished them to have the opportunity of doing,” she wrote.

When the next meeting rolled around in 1920, Mrs. John King Van Rennselaer attempted a coup. She offered a new platform with “the hope that the new ticket would prove more progressive,” according to the New York Herald on January 7, 1920. The conservative board defeated her by a landslide. The New-York Tribune reported, “Attempts of insurgents to elect their ‘revitalizing’ ticket…came to nothing.” Like Mrs. Van Rennselaer, most of those who were elected had Knickerbocker surnames—Walter Lispenard Suydan, Stuyvesant Fish, and R. Horace Gallatin, for example.

In the meantime, since around 1899, the New-York Historical Society established an archeological branch, the Field Exploration Team. On August 31, 1919, The Sun explained that during the team’s two decades, “they have been called to excavations where they have found innumerable things of great historical and sentimental interest.” Among its most important works was the years-long archeological dig at West Point. On July 17, 1921, the New-York Tribune said, “It is now possible for the first time to reconstruct in detail the once powerful citadel of West Point, and picture the daily life in its many forts, redoubts and encampments.”

The third quarter of the 20th century saw the exhibitions take on current issues.

The severe overcrowding and resultant out-of-sight storage of relics that so frustrated Mrs. John King Van Rennselaer and Maria R. Audubon was addressed in 1937, when the architectural firm of Walker & Gillette was commissioned to alleviate the over-crowded conditions. They designed two seamless wings to the north and south.

Nevertheless, the “attic and basement, and everything in between” still held hidden treasures, according to The New York Times on May 18, 1964. In preparation for a special exhibition to celebrate the Society’s 160th anniversary, scholars went on “a treasure hunt.” The article reported, “It has been said that nobody knows just what has been stashed away in the society’s building at 170 Central Park West. Even [director Dr. James M. Heslin] suggested that the wealth of items assembled for the anniversary celebration was surprising.” Included were the astrolabe used by Samuel de Champlain in his 1613 explorations of Canada and New York; the only known life-sized portrait of Peter Stuyvesant, painted in the 1660s; and the John Trumbull portrait of Alexander Hamilton, a copy of which appears on the $10 bill.

After having been its warden for 109 years, in October 1972, the society put on display 433 of the Audubon bird paintings. In reporting on the exhibition, The New York Times commented, “The worth of the watercolors cannot be estimated.”

The third quarter of the 20th century saw the exhibitions take on current issues. On May 27, 1977, The New York Times reported on the exhibition on “Lives of Women.” “The collection is the oldest archive of women’s social and intellectual history in the United States,” said the article. In November 2018, an exhibition about Reconstruction and its aftermath, “Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow,” opened; and in 2019 a series of “micro-shows” reflecting on the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising was staged. One was titled, “Letting Loose and Fighting Back: LGBTQ Nightlife Before and After Stonewall,” and another was “By the Force of Our Presence: Highlights from the Lesbian Herstory Archives.”

Since its aloof beginnings in 1804 at a meeting attended by De Witt Clinton, Anthony Bleecker, Amuel Bayard and Peter G. Stuyvesant, the New-York Historical Society has become more inclusive, user-friendly, and in touch with the issues and concerns of modern life–all of it taking place in the distinguished granite building on Central Park West.

Read about the New-York Historical Society’s former building at Second Avenue and 11th Street HERE.

Read about the New-York Historical Society’s former building at 346-348 Broadway HERE.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

RETURN TO CENTRAL PARK WEST

LANDMARKS TIMELINE

BUILDING DATABASE

DESIGNATION REPORT