West Park Presbyterian Church

by Tom Miller

In 1854 when the 15-member 84th Street Presbyterian Church first opened its doors on the corner of 84th Street and West End Avenue, the Upper West Side, then still called Bloomingdale, was still only scantily developed. The small wooden chapel used by the congregation was for the time sufficient, yet the relentless northward march of New York City was not all that far away.

As the 1880s approached Central Park was completed and the elevated train made its appearance along Ninth Avenue (later renamed Columbus Avenue). The district saw the beginnings of rapid development. Initially, the upheaval caused by the development in the neighborhood had a negative impact on the church. As Broadway (then “the Boulevard”) and other major arteries were cut through, some long-time residents were uprooted. But the little church clung on.

When Anson Phelps Atterbury was hired as pastor in 1879, things would begin to turn around. Atterbury was a member of the socially and financially powerful Phelps-Dodge family which made its fortune in mining. Atterbury’s presence in the pulpit coupled with the steadily-increasing population within the next few years eventually made the little chapel insufficient. On May 30, 1883, the New-York Tribune reported that “D. Willis James has sold to the Eighty-fourth Street Presbyterian Church property on the northeast corner of Tenth-ave. and Eighty-sixth-st., which comprises about five city lots.” The church paid James $30,000 for the large plot—about $600,000 in today’s dollars.

Architect Leopold Eidlitz was hired to design the new church. Not only had Eidlitz been responsible for the original wooden building; he had by now established a firm reputation for himself with works like his magnificent Temple Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue and St. Peter’s Church in the Bronx. For the still-small congregation, Eidlitz produced a small brick chapel in the Victorian Gothic style on one side of the building site.

On November 10, 1884, The New York Times reported on the completed structure. “The edifice is a brick structure, 35 by 85 feet in dimensions. The congregation room is upstairs, and the pews are finished in oak. The walls are terra cotta and bronze. The lower room is used for the Sabbath school, and it is finished in cherry.”

“The church had a hard struggle for existence by reason of the fact that the Bloomingdale neighborhood was largely depopulated by the laying out of new streets, the Boulevard and the Riverside Drive, but it held its own and began to prosper with the ministration of the present Pastor, who was ordained five years ago.”

The New York Times recalled the difficulties the little congregation had endured. “The church had a hard struggle for existence by reason of the fact that the Bloomingdale neighborhood was largely depopulated by the laying out of new streets, the Boulevard and the Riverside Drive, but it held its own and began to prosper with the ministration of the present Pastor, who was ordained five years ago.”

Now, however, the church was thriving. The building was entirely paid for before the doors were opened. Five ministers were present during the dedicatory service on November 10 and in his sermon, the Rev. Dr. Charles S. Robinson reminded the congregation that the building was less important than the souls of those who worshiped within it. He likened the structure to a lighthouse and told the story of a keeper who was reprimanded for tending the lights rather than trying to save the lighthouse during a great storm. “The Government put me here to save ships, not the lighthouse,” was his response.

Robinson took the opportunity to gently chastise the congregation about giving sparingly to the church. The Times quoted him “The interest on the value of a sealskin sacque is $36 a year, but no woman will give that amount for pew rent.”

The building was used for other gatherings as well. Three months later, on February 12, 1885, General Alexander S. Webb, President of the College of the City of New York, presented an illustrated lecture on “Gettysburg;” a subject still remembered by many of the neighborhood residents.

That the church never intended that Eidlitz’s brick structure be its permanent home was evidenced in testimony made on April 9, 1887, in the State Supreme Court. There was some untidy business going on after William E. Stokes, a relative of Anson Phelps Atterbury, sued the church and the Phelps Mission. Court papers said, “That the said 84th Street Presbyterian Church now professes to be the owner of four lots of ground on the north-east corner of 86th Street and 10th Avenue, upon which there is now erected a chapel; that it has no regular church edifice or building whatever, but uses the said chapel for the purposes of church service until a church shall be erected…”

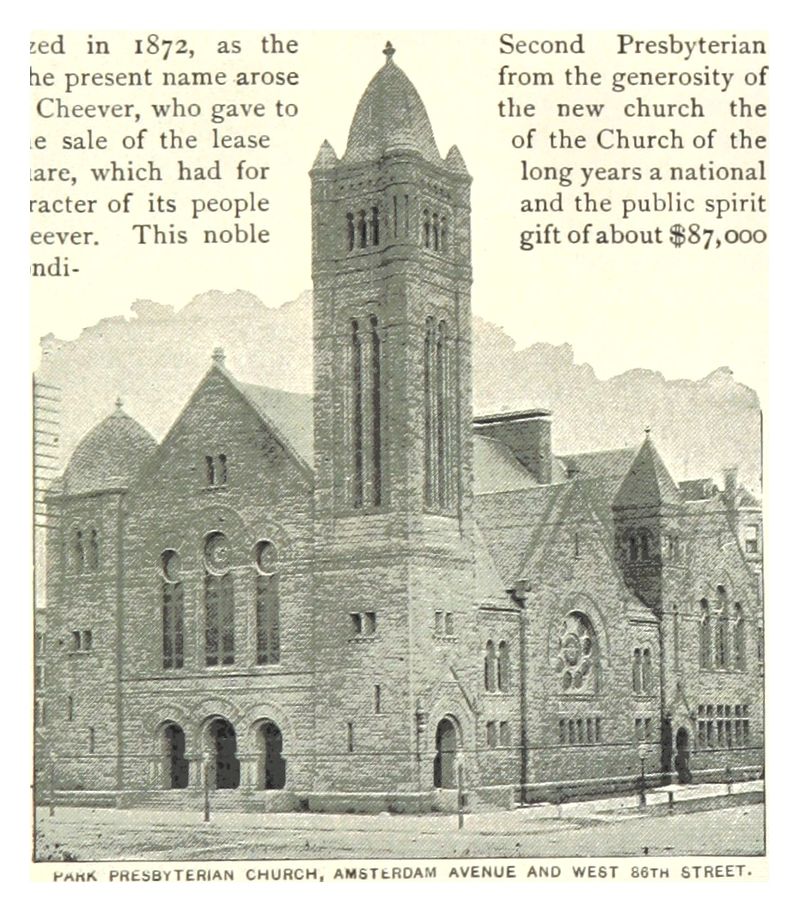

Two years after that description, the congregation deemed itself ready for a “regular church edifice.” Architect Henry Kilburn received the commission to design a large main church building. He was given the direction of incorporating the existing chapel into the design. When he was finished there was no hint of Eidlitz’s Victorian Gothic structure hidden in his own Romanesque Revival design.

The church had, by now, been renamed the Park Presbyterian Church. Its new structure, completed in June 1890, was a massive medieval-looking pile of ruddy-colored sandstone. Hefty arches and rugged stonework supported gables and towers—a delight of asymmetrically-placed openings and angles. Anchoring it all was a monumental corner tower culminating in a bell-shaped cap.

The little church of 15 congregants had come a long way in half a century. The new building had seats for 900 worshipers. The first service in the building, a month before official completion, was conducted with appropriate flourish.

The church, mostly through the efforts of Atterbury, was at the forefront of social reform and activism. He was an insightful author, writing books like “Islam in Africa: its Effects—Religious, Ethical, and Social—Upon the People of the Country,” and had little patience for intolerance and racism. In the 1880s New York City was overtaken by a rampant prejudice again the Chinese, often referred to as “Mongolians.” A reporter from the New York Sun in 1880 wrote “The lower end of Mott Street is an unsavory locality, disagreeably close to the associations of vice, crime, and poverty by reason of which the Chinese are unjustly but naturally compelled by mere proximity to bear a worse reputation than they deserve.”

Atterbury responded to the “worse reputation than they deserve” by overtly campaigning for Chinese worshipers.

On March 13, 1911 readers of The Evening World got the news that the West Presbyterian Church on 42nd Street was to “give way to a modern skyscraper.” The newspaper said, “The ‘Millionaire’s Gate to Heaven’ will be closed when the famous West Presbyterian Church, which has counted among its parishioners Russell Sage, Jay Gould, J. Hood Wright, Alfred H. Smith, E. Francis Hyde, Seth Thomas, H. M. Flagler, Robert Jaffray and a score of other wealthy men, representing $750,000,000, to which fact is due its irreverent title, shuts its doors.”

With no church edifice, the congregation made plans to merge with Park Presbyterian. Three months later, on June 11, the merger was complete and The New York Times reported that “The new organization will now be known as the West-Park Presbyterian Church, worshipping at the old Park Church.”

On March 13, 1911 readers of The Evening World got the news that the West Presbyterian Church on 42nd Street was to “give way to a modern skyscraper.” The newspaper said, “The ‘Millionaire’s Gate to Heaven’ will be closed…”

Later, The Sun heaved a sigh of relief when it was able to tell readers “When the West Presbyterian Church moved up to the West Side and joined with the Park Presbyterian the choir remained intact.” The newspaper reported on the high-class choir which included soprano Bertha Kinzel, who had recently sung with the Boston Symphony Orchestra “and with nearly all the oratorio societies of the East;” and singers from the Metropolitan Opera and other illustrious organizations.

Throughout the 20th century, West-Park Church would continue Anson Phelps Atterbury’s tradition of responsible activism—standing up for civil rights, nuclear disarmament, same-sex marriage, and gay rights, and criticizing the Vietnam conflict. When the AIDS epidemic hit New York City, it was the original site of God’s Love We Deliver, the organization established to deliver meals to AIDS patients.

Around 2008 the magnificent Romanesque Revival building, considered by many to be the best example of the style in a religious building in the city, was threatened. It was not outside developers who wanted the building demolished—it was the congregation. The structure, nearly a century and a quarter old was suffering. The congregation’s solution for the seeping water and peeling paint was to convert part of the building into apartments. The drafty and uncomfortable sanctuary was abandoned.

While the church poked around at building and renovation plans, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission stepped in. Against the wishes of the church, the building was designated a New York City landmark in 2010; effectively squelching any conversion plans. Little by little the church began repairs—starting with a new boiler so congregants no longer had to wear coats during services.

In keeping with West-Park’s long tradition of activism, Rev. Robert Brashear offered the building to around 60 Occupy Wall Street protestors as a place to sleep late in 2011. The minister soon found out that not all good deeds go rewarded when, during the first week, his computer disappeared.

The Occupiers promised Rev. Brashear to reimburse him for the stolen computer; but his compassion was strained further a few weeks later when, in January 2012, the bronze lid of the baptismal font was stolen. Brashear told the group that he did not believe in collective punishment, but he did believe in collective responsibility.

The group was ousted from the church; although the pastor stressed that he still supported the protest.

Henry Kilburn’s masterful and rugged West-Park Church is little changed after more than a century of standing sentinel at 86th Street and Amsterdam Avenue—a masterpiece of Romanesque Revival architecture.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

building database

Landmarks Timeline

Explore Houses of Worship

Designation Report

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the non-profit institutions currently at 165 West 60th Street:

West Park Presbyterian Church

Meet Debby Hirshman!

The Center at West Park