The 1894 “West End Synagogue” aka Ukrainian Orthodox Cathedral of St. Volodymyr in NY

by Tom Miller

On January 28, 1921 The American Hebrew reminded its readers of the history of Congregation Shaaray Tefila. “The congregation was organized in 1845. Its members were all immigrants from England or sons of British immigrants. Its first place of worship was on Franklin street near Broadway, a section which in 1845 was the residential center of New York.”

In 1871 the congregation merged with Congregation Beth-El. It was around this time that the strict orthodox restrictions were loosened—organ music was introduced, females were admitted into the choir, and men and women worshiped together.

As the residential districts changed, Congregation Shaaray Tefila moved to Wooster Street, to West 34th Street, and to 44th Street. The American Hebrew noted “New York continued its uptown trend. In 1892, the Forty-fourth street building was sold and Carnegie Hall was selected as the temporary place of worship…Congregation Shaaray Tefila was the first organization to hold religious services in Carnegie Hall.”

The trustees were planning the next move at the time. The Upper West Side was Manhattan’s newest and perhaps most exciting new neighborhood. Three building plots—Nos. 156 through 160—were procured on West 82nd Street between Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues, and architects Brunner & Tyron were commissioned to design the congregation’s new home.

For decades, synagogue architects had turned to the Moorish Revival style. Gothic Revival was too closely linked to Christian churches and Greek Revival had no historic context with the Jewish religion. Moorish or Byzantine motifs, on the other hand, reflected the pre-Inquisition period when Jews enjoyed relative freedom in Spain.

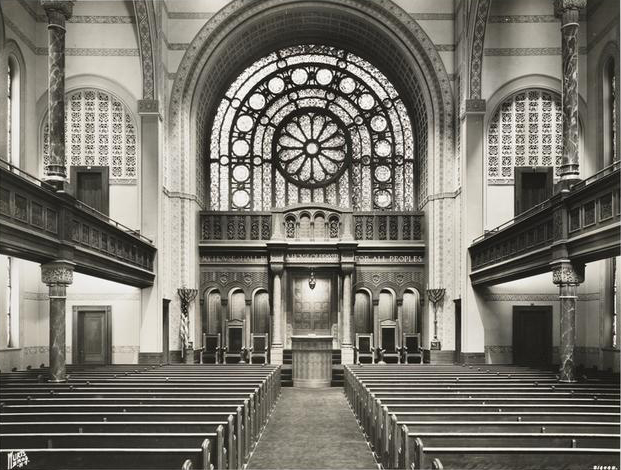

Arnold W. Brunner was gradually turning away from the style, and his Congregation Shaaray Tefila, completed in 1894, reflected his preference for the neo-Classical style in synagogue architecture. Nevertheless, he liberally splashed its symmetrical façade with Moorish touches—cusped arches, carved Moorish designs and alternating bands of lighter and darker stone and brick above the openings. The grand split staircase which led to the entrance arcade along with the imposing architecture in general was evidence that Shaaray Tefila was by now one of the wealthiest congregations in the city.

Among the tributes read were those from President Herbert Hoover who called Mosessohn “my friend”

The 82nd Street synagogue would be the scene of the funerals of some of Manhattan’s most influential citizens. On June 3, 1921 the funeral of Dr. Simon Baruch, father of millionaire financier Bernard M. Baruch, was held here. Baruch was one of America’s most distinguished physicians. He performed the first successful operation on a perforated appendix, lobbied for the establishment of free public baths in New York City, and was considered the pioneer in scientific hydrotherapy.

Another funeral of note was that of David Mosessohn, editor of The Jewish Tribune. More than 1,000 persons filed into what was popularly known as The West End Synagogue on December 18, 1930. Among the tributes read were those from President Herbert Hoover who called Mosessohn “my friend,” from former Governor Al Smith, Lieutenant Governor Herbert H. Lehman, Chief Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo, Felix M. Warburg, and other judges, politicians and businessmen.

Later that year, on December 26, Lily Montagu spoke here. The daughter of Lord Swaythling, The New York Times called her “a strong advocate of liberal Judaism.” Her invitation to speak was evidence of the congregation’s open-minded viewpoint of its religion.

Within a few months its focus would turn overseas. On April 14, 1931 The New York Times reported that former Ambassador to Germany, James W. Gerard, had addressed the congregation the day before. He said Adolf Hitler had “reverted to the attitude of the Middle Ages.” He also attacked the Soviet Government for its attitude towards Jews. Those who attended the speech that day had no hint of the horrors that Germany and the USSR were about to launch.

Five years later, as German Jews desperately tried to flee their homeland, Rabbi Hyman Judah Schachtel compared their suffering to the Jews under Pharaoh more than 3,000 years earlier. He said that the “new exodus” was here and “the day is not far off when we shall rejoice in another great deliverance from the house of bondage.” But the hatred of Jews spawned by the Nazis would soon reach West 82nd Street.

Two decades earlier, while another world war raged in Europe, the congregation hired Alexander Kinderman as the building’s caretaker. Kinderman, a Roman Catholic, was given a small apartment in the east tower. Jewish tradition required the employing of non-Jews to fill the position so mechanical operations—like turning lights on and off—during the Sabbath could be done. Kinderman was well-liked and trusted. He earned $132 a month and reportedly often handled thousands of dollars in cash in his duties.

On March 15, 1937 large orange swastikas were painted on Temple Rodeph Sholom, just a block away on West 83rd Street. Less than two weeks later, on March 27, Kinderman smelled smoke at around 1:45 in the morning. He discovered two fires in the basement level. In a classroom, chairs had been piled and set on fire; and in the assembly hall the curtain over the stage had been ignited. Both fires were successfully extinguished before much damage could be done.

At 10:00 that morning congregants celebrated the second Passover Seder. The synagogue was empty by 1:00 in the afternoon. Kinderman told authorities that after he locked up he went back to his rooms. At 3:15 a passerby reported a major blaze.

By the time the conflagration was extinguished the entire south end of the sanctuary was “wrecked,” the $25,000 pipe organ was severely damaged and, according to The Times, the fire “demolished the valuable scroll-work Russian Walnut Ark of the Covenant and destroyed eighteen hand-illuminated Torah, or books of the law, kept in the Tabernacle.” The damage amounted to $80,000—nearly $1.5 million today.

Fire Commissioner John J. McElligott was “convinced that the fires were deliberately set” and announced “the dastardly culprit or culprits must be apprehended.”

The dastardly culprit was indeed caught and his identity shocked and dismayed the congregation. On March 31 the Fire Commissioner announced that after 10 hours of questioning Alexander Kinderman had confessed to setting all three fires. Commissioner McElligott said the arsonist explained he was “seized by an uncontrollable impulse.”

At Kinderman’s sentencing Harry M. Wessel, president of synagogue, urged leniency. The judge was little moved. He sentenced Kinderman to up to 10 years in Sing Sing.

The West End Synagogue was repaired and refurbished. It was rededicated on December 17, 1937. Back in its home, the congregation again turned its attention to the Nazis. On November 12, 1938 Rabbi Herbert S. Goldstein asked “Will the nations of the world sit idly by and remain passive while Germany is continuing in its inhumanitarian treatment of the Jew, a child of God? Nazism is not a Jewish problem; it is a Christian problem; it is a world problem.”

Today it continues to serve the Ukrainian Orthodox community as the Ukrainian Orthodox Cathedral of Saint Volodymyr in New York.

In his sermon on August 26, 1939, Rabbi Hyman J. Schachtel seemed to have lost immediate hope, lamenting “peace is gone for our time.” But he urged his congregants to make a better world after the war. “Let us who saw a world die bequeath to the coming generation a heritage of wisdom, a legacy of truth. Let them know how we hated one another and delighted in armaments; how we rejected spiritual ideals and rejoiced in material advancement disregarding the consequences to human welfare. Let us leave them an honest record of our sins, and the fervent prayer that they will learn from us what not to do.”

Like the situation of desperate refugees fleeing near-certain death in Syria, Kosovo and Afghanistan in 2015; the free world was burdened with Jewish refugees in 1939. And, as is the case today, there was a significant push by some to prohibit their acceptance on American soil. On October 21, 1939 Rabbi Schactel addressed what a newspaper called “the refugee problem.”

“The only kind of change we ought to have in the United States is the normal, healthy growth of public opinion and decision which gradually extends the principles of democracy into every part of the life of the citizens.”

Among the West End Synagogue’s congregants to fight in Europe was First Lieutenant Martin Strauss. The pilot was recognized as the hero of 24 missions before he was shot down in a Flying Fortress raid on Bremen on April 17, 1943. Although he was officially termed “missing in action,” there was little hope of Lt. Strauss’s return.

On October 23 that year a military honor guard was present at the West Side Synagogue as Colonel Harold W. Beaton pinned the Air Medal and the three Oak Leaf Clusters on the airman’s mother, Mrs. Arthur Strauss. The awards were for “courage, coolness and skill of the highest order.”

The Times mentioned “Lieutenant Strauss was a sophomore at New York University when he enlisted. He became a second lieutenant after his twentieth birthday.”

On September 20, 1959 Gerard Oestreicher, building committee chairman, announced that Congregation Shaaray Tefila “is moving into an old motion picture theater building.”

The former West End Synagogue was converted for use by the Ukrainian Autocephalic Orthodox Church.

Today it continues to serve the Ukrainian Orthodox community as the Ukrainian Orthodox Cathedral of Saint Volodymyr in New York. It is named for Vladimir I, or Volodymyr I, Prince of Novgorod, the Grand Prince of Kiev. The congregation carefully and sympathetically renovated the interiors for Christian purposes; while retaining the sumptuous décor.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT