Trinity School: 139 West 91st Street

by Tom Miller

Looking upon the looming Trinity School, especially in the darkening hours, the passerby can imagine Emily Bronte’s Catherine Earnshaw erupting from the front doors at any second calling out for Heathcliff. The venerable institution, however, is romantic only in its architecture.

The private school’s history stretches back to 1709—the fifth oldest school in the United States. That year William Huddleston opened a charity school for both boys and girls, for Trinity Church. Coeducational learning was an astonishingly liberal concept Trinity School was such facility in the colonies. Huddleston worked under the auspices of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts—“foreign parts” being anything outside of England.

For four decades, the classes were held either in City Hall, the schoolmaster’s own home, or in the ample steeple space of the church. It was a charitable institution that instructed the poorer children alongside those of more fortunate families. After being schooled in reading and writing, students were usually placed into apprenticeships, thereby assuring them a living and means to become useful citizens.

It was a charitable institution that instructed the poorer children alongside those of more fortunate families.

Two months after a new school building was constructed directly across from Trinity Church it burned to the ground and was necessarily rebuilt. King’s College, later to become Columbia University, started out on the first floor of the new 1749 building.

Trinity became an all-boys school in 1838. By the last quarter of the 19th century Lower Manhattan was the bustling business center of Manhattan—a far different neighborhood from that of brick and wooden houses in 1709. The need for schools in the northern developing parts of the city now outweighed the need downtown.

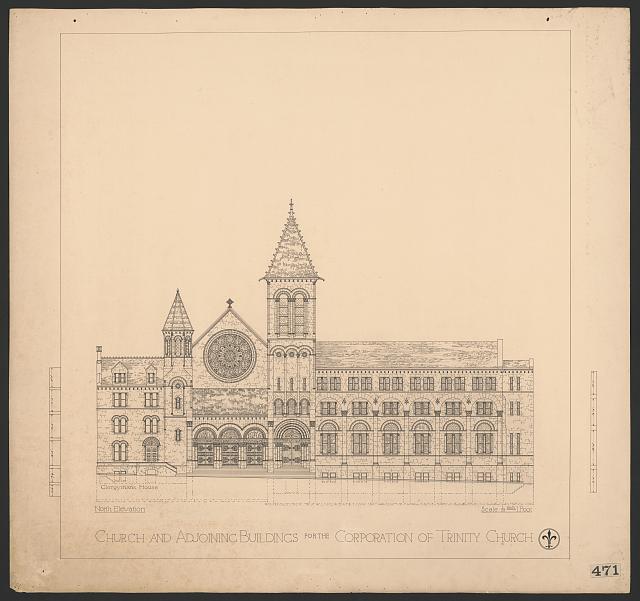

Trinity Church had already established the St. Agnes Chapel complex far to the north on the Upper West Side. In 1892, the handsome St. Agnes Parish House, designed by William Appleton Potter, was completed. A year later Trinity purchased five lots adjacent to the Parish House and commissioned Charles Coolidge height to design what The New York Times predicted would be “one of the finest school buildings in the city.”

The cornerstone was laid by Dean Hoffman of the General Theological Seminary on October 18, 1893. The Critic reported that it would be of “the scholastic type of English renaissance.”

Stretching from 139 to 147 West 91st Street, the completed building was dedicated on February 3, 1895. With an estimated cost of $200,000, the building came in about $30,000 under budget. The New York Times called it “a handsome four-story structure of brownstone, and is admirably adapted for scholastic purposes.” The ground floor held a large assembly room, library, primary department classrooms and the Trustees’ rooms. Classrooms filled the second and third floor, while the fourth was mainly an “elaborately equipped gymnasium.”

Trinity School, after nearly two centuries of existence, was still a church-run school. The New York Times noted, “Throughout its entire history, Trinity School has never consented to divorce scholastic from religious training.” And during the dedication ceremonies, Bishop Rulison of Central Pennsylvania added that “It seems to me that a church school like this stands for something better than does a school that merely teaches people how to get along in the world…You cannot make character that will stand high, broad, and strong unless a religious influence has been exerted upon the mind of the pupil.”

Haight reflected this in the style of the new building—today called English Collegiate Gothic. He was also deeply concerned about its functionality and the conditions in which the boys would spend so many hours. By extending the bays at either end outward, he created a grassy courtyard for the students. The large dimensions of the windows flooded the classrooms with light and, when opened, increased the ventilation. The building was declared “completely fireproof” and was lauded for its excellent sanitary, heating and ventilating systems.

The students received not only quality schooling at Trinity, they gained a reputation for upstanding character. One young man relied on the weight of the school’s name when attempting to find summer work in 1897. He advertised in The Churchman “A boy, in his eighteenth year, would like situation as Companion and Caretaker of small boy through vacation. Could teach boy to swim, sail, and row, and refers to Dr. Ulmann, Trinity School, W. 91st St., New York.”

…“It seems to me that a church school like this stands for something better than does a school that merely teaches people how to get along in the world…You cannot make character that will stand high, broad, and strong unless a religious influence has been exerted upon the mind of the pupil.”

The morals intrinsic to the school were evident a year later when a student named Mohr gave a false date of birth so he could compete in the junior events of the annual track team championships. When the Interscholastic Athletic Association discovered the fraud and pressed charges against Trinity School, young Mohr learned a lesson in ethics.

Trinity’s rector, Dr. A. Ulmann, announced that then the boy admitted he had lied he was immediately suspended. “He will most likely not return,” said Ulmann, “as such playing fast and loose with the truth is a capital crime in our school.”

By 1915, the school that had started out teaching colonial children how to make a living was now an exclusive institution. The Handbook of Private Schools noted that year that the entire enrollment—from primary to college preparation—was 300 boys. A full 80 percent of its graduates entered top colleges every year

Trinity School continued through most of the 20th century adapting to certain changes and avoiding others. In 1968, it separated from Trinity Church, choosing to become non-sectarian. Then, in 1971, female students were admitted for the first time in 133 years.

Yet Trinity School still requires at least one semester of religious studies and keeps on staff an Episcopal priest paid by Trinity Church. While most high schools across the country have dropped Latin and Greek from their curricula, Trinity’s Classics Department is considered one of the best in the United States with about 40% of the students enrolled in one or both of the ancient languages.

In August 1989 the Landmarks Preservation Commission designated both the Trinity School building and St. Agnes Parish House—which had become part of the school in the 1940s—a joint New York City landmark. The unflagging high level of academic instruction was reflected when Forbes Magazine deemed Trinity the best college preparatory school in the United States in April 2010.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com