125 Riverside Drive

by Megan Fitzpatrick

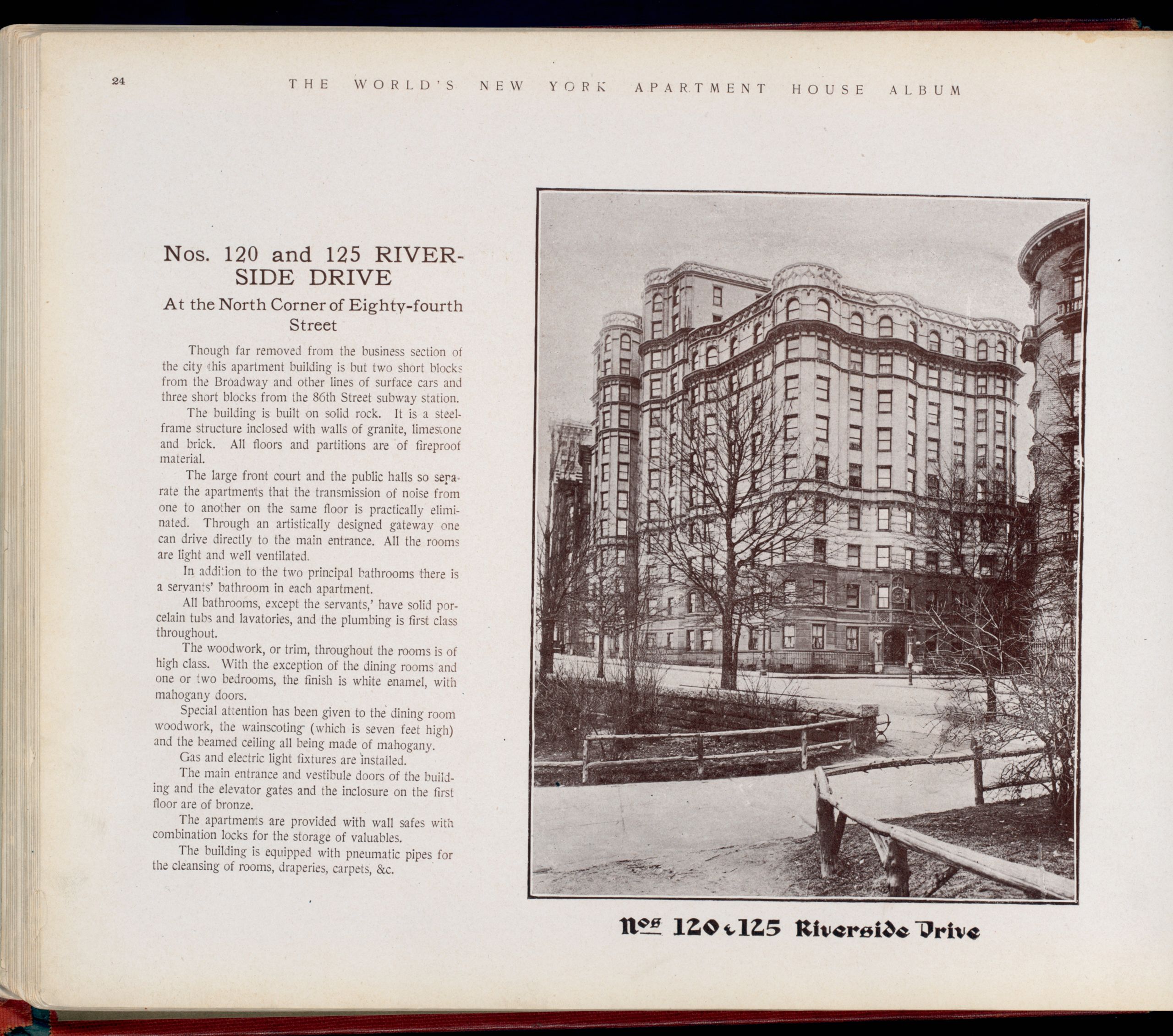

Four years after the completion of the nine-story apartment at 120 Riverside Drive, designed by George Keister, architect and developer Samuel B. Ogden eyed up the neighboring empty plot for potential. Instead of designing a totally new building, Ogden decided to take inspiration from his next-door neighbor, or rather, make a complete copycat design.

Samuel B. Ogden joined his father in the architectural firm A. B. Ogden & Son in 1885. Two years after his father‘s death in 1895, Samuel established his own firm S. B. Ogden & Co. in association with John H. Tomlinson. Over the course of the early 20th century, S. B. Ogden‘s firm designed a diverse array of buildings, including stables, factories, and warehouses, but particularly multiple dwelling buildings like flats and tenements, in Brooklyn and Manhattan. On the west side, among his notable works are 2733-2737 Broadway, 306 West 102nd Street and 125 Riverside Drive. Two years after completing his Riverside Drive project Ogden closed the firm in 1909 and retired from practice.

Despite some floorplan differences, and towering two stories taller, Ogden planned for his building to be a carbon copy of Keister’s 1899 design. The apartment was faced in beige brick above a two-story limestone base, to match its neighbor. The neo-Medieval style and ornate carvings, including Gothic corbels below the fourth floor, and a lacework-style parapet, continued across from No. 120.

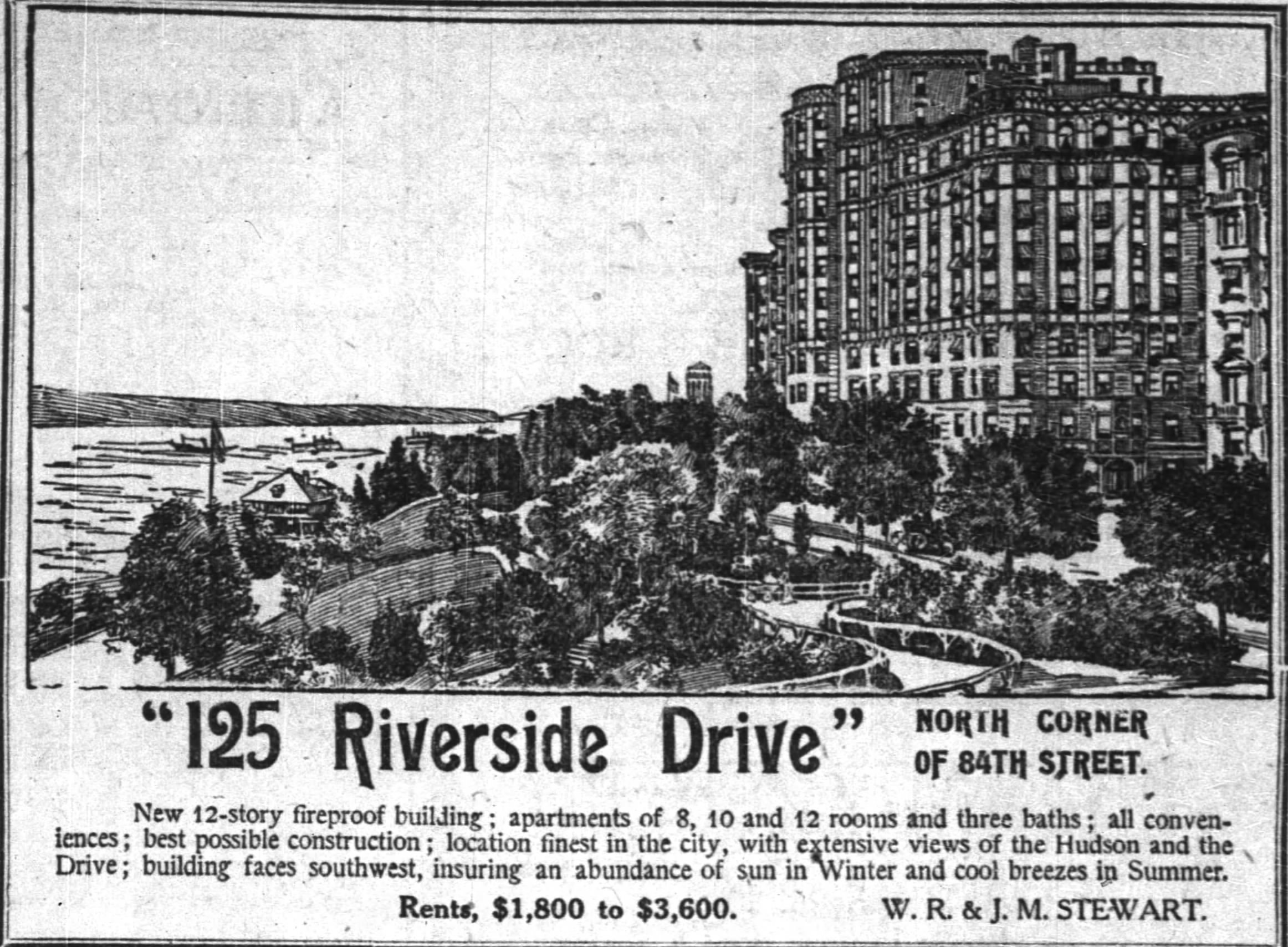

The apartment building was completed in 1907 and the first advertisements were placed in the newspapers. The New York Times announced on August 26, 1907, that the new 12-story “fireproof building” had apartments featuring an impressive number of 8, 10, and 12 rooms and three baths for sale. The highlights were the “extensive views of the Hudson and the Drive,” but also its south-west position, which guaranteed “an abundance of sun in Winter and cool breezes in Summer.” At first, rent ranged between $1,800 and $3,600 a year.

Despite some floorplan differences, and towering two stories taller, Ogden planned for his building to be a carbon copy of Keister’s 1899 design

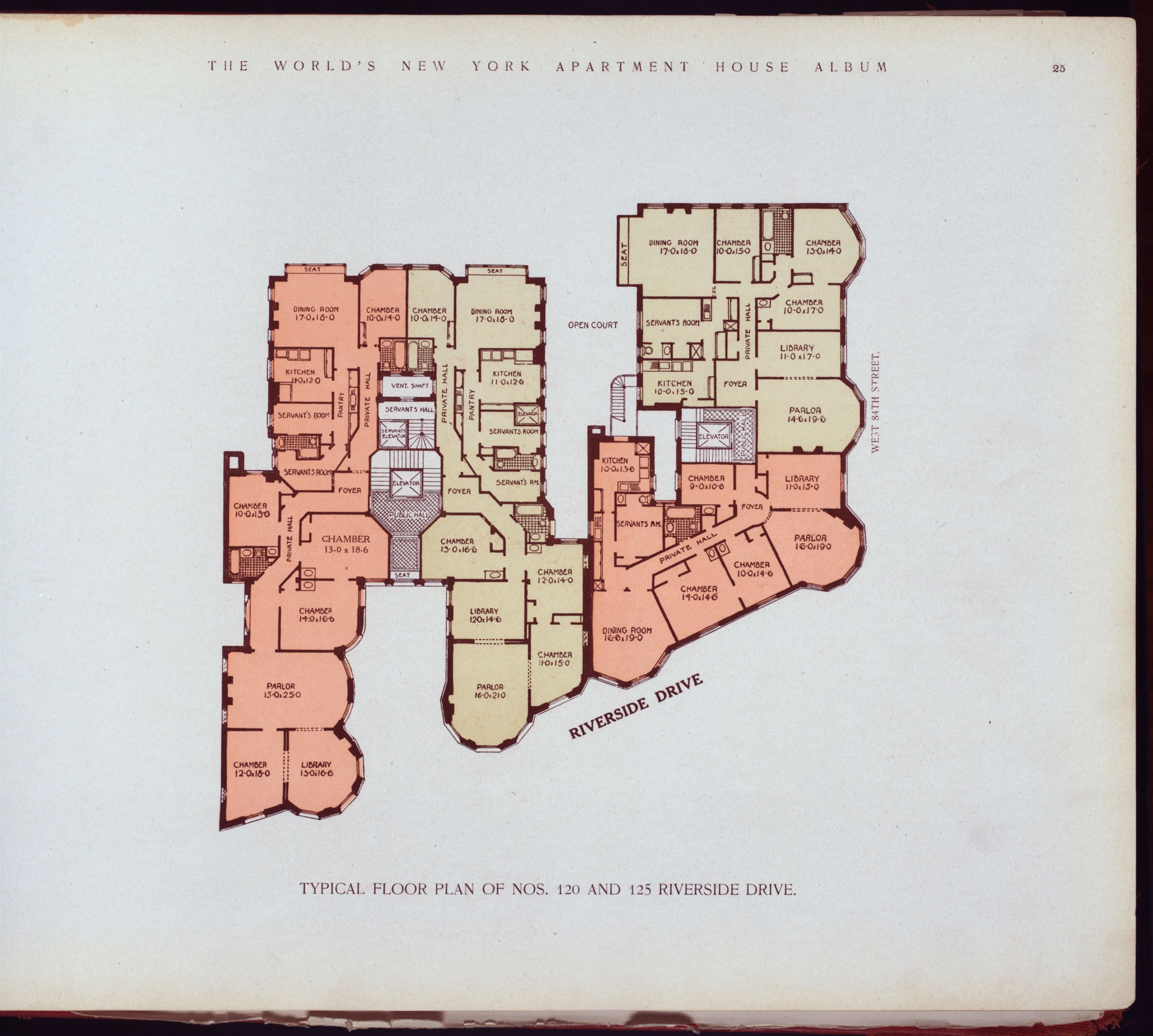

By 1910, both 120 and 125 Riverside Drive were referred to as one building. In a piece published in The World’s New York Apartment House Album (1910), both buildings that were “far removed from the business section of the city,” were listed as a single complex. They included a detailed floor plan, which shows both buildings connected by an adjoining wall and shared open court. The newer 125 Riverside Drive boasts a slightly larger footprint with a more elaborate and attractive front court and public halls. “Through an artistically designed gateway,” the piece explains, “one can drive directly to the main entrance.”

Among the 8-12 rooms originally planned for each apartment, were several bedchambers, a parlor, a kitchen, a library, and servants’ rooms. “In addition to the two principal bathrooms, there is a servants’ bathroom in each apartment. All bathrooms, except the servants,’ have solid porcelain tubs and lavatories, and the plumbing is first class throughout.” Special attention was given to the interior woodwork, particularly the seven feet high wainscoting and mahogany wood doors, and beamed ceilings. The architects had safety and modern technology in mind when they installed wall safes in each apartment and pneumatic pipes to ensure the “cleansing of rooms, draperies, carpets, &c.”

By the early 1920s, a rental crisis seemed to have hit 125 Riverside Drive. A realtor, William C. Freeman, claimed to have lived at No. 125 but reluctantly gave up his apartment in October 1920, because his rent increased from $2,220 to $3,420 in one year. He went on to say the asking price for 1921 was $4,200 a year. His resolution? He bought property in Norwood Gardens and encouraged renters to follow suit in his very convincing, yet hard to entirely believe, advertisement in the newspaper.

Throughout the decades, many well-to-do families took up residence at 125 Riverside Drive, attracted to the top-class amenities on offer and location. An Olympic runner who competed in the controversial 1936 Berlin games, Edward T. O’Brien, lived in the building as did a member of the “illustrious” Perry family from Binghamton, Mrs. William G. Phelps, granddaughter of the famous architect who built the State Capitol at Albany, Isaac G. Perry.

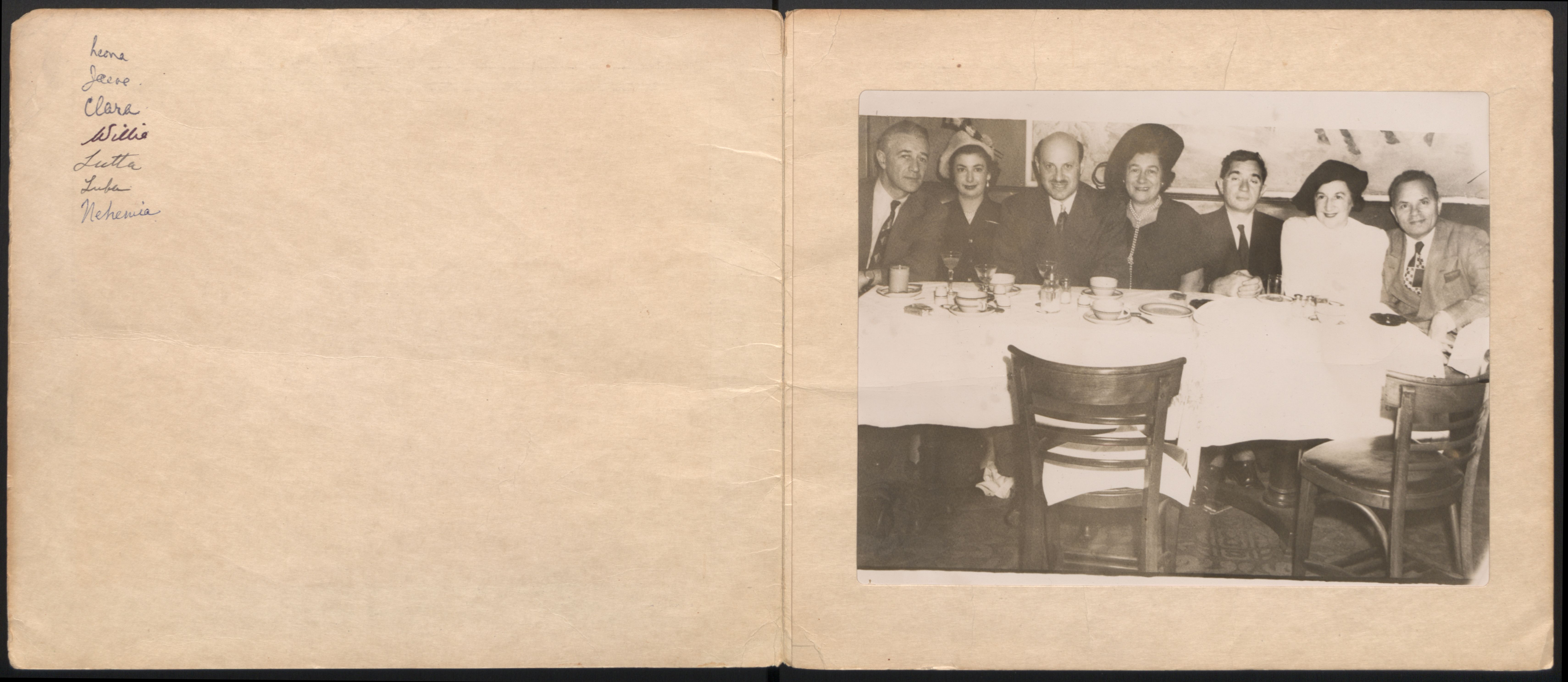

Two of the most significant residents were the Robinson brothers. Jacob and Nehemiah Robinson were Jewish émigrés who fled Lithuania and settled in New York in 1940, a month before Soviet forces would occupy and later annex the region. Jacob Robinson was a lawyer and later politician, elected to the Second Lithuanian Parliament in 1923. Before coming to the U.S., he was involved in the founding of the World Jewish Congress which sought to act as a “diplomatic arm of the Jewish people.” When he reached America, he founded the Institute of Jewish Affairs, a scientific and research organization attached to the American and World Jewish Congress. They emigrated together with Jacob’s wife, two daughters, and secretary Luba Stone. With him, Jacob brought his cast iron typewriter with a Cyrillic keyboard that was manufactured in the U.S., but made for a foreign market.

Both Jacob and Nehemiah, also a lawyer, for years conducted research for the organization focusing on the fate of Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe and the question of reparations and indemnification. In 1952, Jacob drafted the reparations agreement between Israel and the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG). Nehemiah, who succeeded his brother as director of the Institute, also drafted agreements between the FRG and the Claims Conference as well as the FRG’s Indemnification Law. As the leading expert on prosecuting Nazi war criminals, Jacob was a consultant to Justice Robert H. Jackson at the Nuremberg trials, and the legal mind behind the prosecution at the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem in the early 1960s, serving as special assistant to the Attorney General. Nehemiah passed away at home in 1964 and Jacob followed suit over a decade later in 1977, leaving behind a legacy of civil service work to his community.

With him, Jacob brought his cast iron typewriter with a Cyrillic keyboard that was manufactured in the U.S., but made for a foreign market

Ownership of the building exchanged hands many times over the years, which ultimately harmed the building physically. In January 1937, Metropolitan Life Insurance Company acquired both buildings in foreclosure proceedings at auction for $400,000. During this ownership, which lasted from approximately 1937 to 1945, it can be deduced that the historic parapet was removed. Historic photographs from 1940 onwards capture the building without its parapet. Additionally, reporting a new acquisition of the building by Boston Associates, The New York Times noted in August 1945 that Metropolitan Life altered both buildings “some time ago.”

Despite the unceremonious removal of the parapet in the 40s, and ongoing maintenance work in the present day, Ogden and Keister’s pair of buildings still reflect their neo-Medieval origins.

Megan Fitzpatrick is the Director of Preservation and Research at Landmark West!