St. Paul the Apostle Church

by Tom Miller

On Saturday, January 6, 1872 the Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide made an unexciting note that alterations were proposed for an existing church building in Manhattan. “One brick church, north side of Fifty-ninth street, 270 feet west of Ninth avenue…two stories and basement” was to be extended and “interior alterations also to be made, the changes proposed involving an expenditure of $53,000; trustees Church of St. Paul the Apostle, owner.”

The rather pricey renovations of the small 1859 church in a still somewhat undeveloped area of New York’s West Side was just the start of a construction project that would continue for a century.

The Memorial History of the City of New-York would record in 1893 that “The organization of the first American order of priests, by Fathers Hecker, Hewit, Baker, Deshon, and Walworth, ‘the missionary priests of St. Paul the Apostle,’ occurred in 1858-9; they erected a church and convent in Fifty-ninth street, near Ninth Avenue, in 1859.”

Father Isaac Thomas Hecker had been elected superior of the Paulist Fathers a year earlier and he was instrumental in acquiring the 32 building lots on Ninth Avenue between 59th and 60th Streets in 1859 for $40,000—about $850,000 today. Despite the rather remote location, when the cornerstone for the brick building was laid on June 20, 1859, approximately 15,000 people were in attendance. The no-nonsense church was completed within five months and was described by the New York Herald as “constructed with regard to strength and durability rather than ostentation and mere outward show.”

Now, in January 1872, the once-distant neighborhood was quickly developing and the Paulist Fathers looked to enlarge their facilities. (Although American Architect and Architecture commented that still “Many streets nearby were not then cut through; many of the scattered dwellings were shanties.”)

Father Hecker, who had traveled widely, envisioned a grand church edifice that would rival the cathedrals of Europe, or perhaps more importantly, the white marble St. Patrick’s on Fifth Avenue now nearly completed. To execute his grandiose plans, Father Hecker reached out to a French architect to do preliminary designs for the new church.

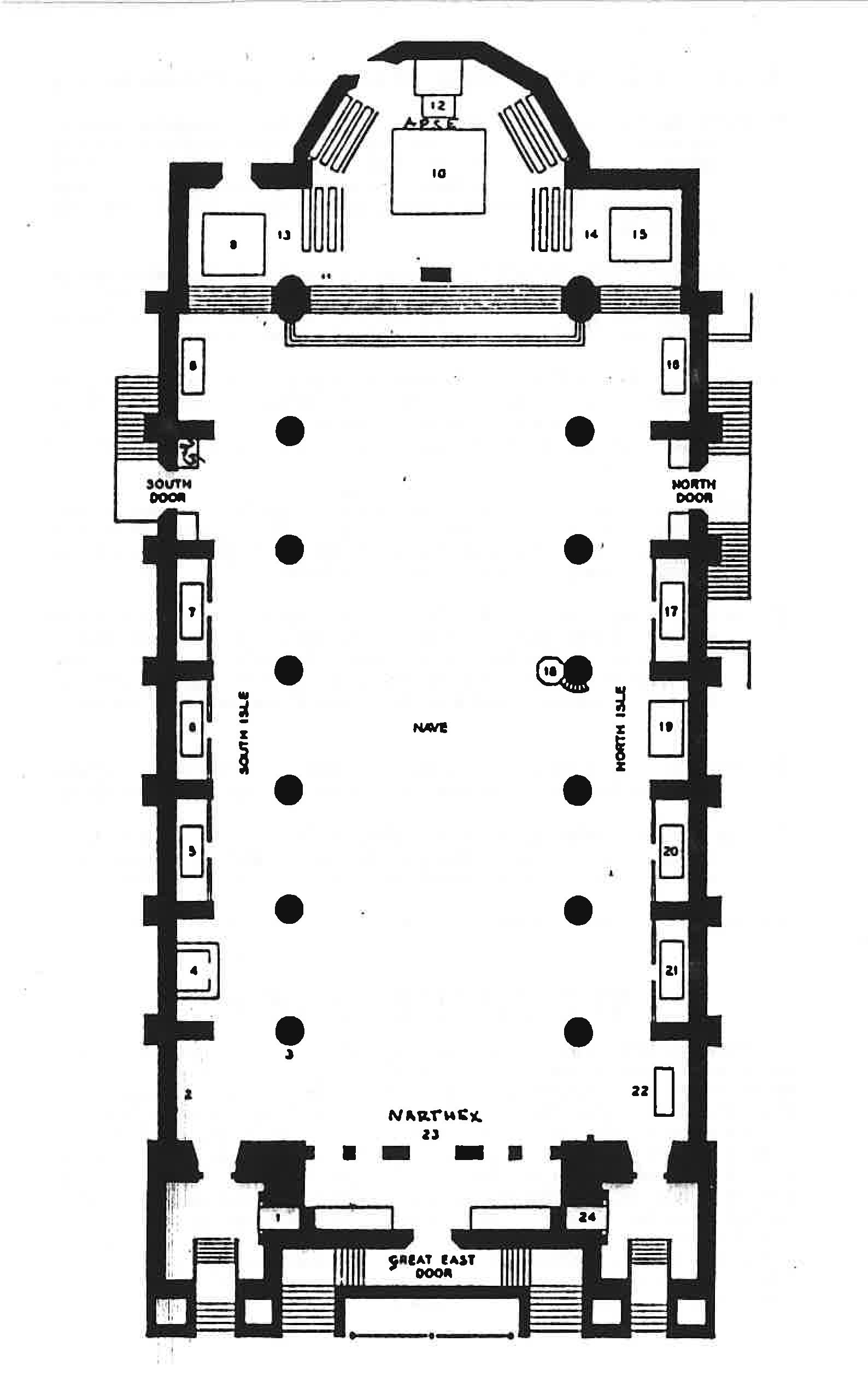

American Architect and Architecture later recalled “The principal points settled by Father Hecker were that the nave should be 60 feet wide, that there should be no seats in the side aisles, and that all the light should come from above…He also contemplated elaborate decorations, both on the interior of the church and upon the exterior.”

Hecker’s assistant superior general, Father Alfred Young was put in charge of overseeing the initial process. Immediately the first instance of what would be decades of dissension and disagreement arose. Likening the plans to a “heathen” mausoleum and saying they “would never be mistaken for a Catholic church,” he looked closer to home for an architect.

Irish-born Jeremiah O’Rourke had come to the United States in 1850 and was responsible for several Catholic churches in New Jersey, including the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Camden. Father Young gave him the direction to design a massive church in a plain Gothic style. Four years would pass before plans were submitted and the cornerstone laid. With the expected hype of the Victorian press, a local newspaper announced the church would be “a conspicuous object in the city’s landscape.”

The pair became involved in a heated stand-off that was settled when two experts were called in for consultation. They agreed with Deshon and Jeremiah O’Rourke returned across the Hudson River, leaving the project in the hands of Rev. George Deshon, now architect in charge as well as chief mechanic.

Timing of the project could not have been worse in one respect. The great Financial Panic of 1873 had thrown the country into a massive depression.

Some money was saved by using recycled materials. The 8-foot thick walls were originally designed to be clad in red Connecticut granite. But as the church began rising, a major civic demolition project was taking place. The stone embankment of the 1842 Croton Aqueduct uptown was already being dismantled when Father Deshon and two other priests were riding in an Eighth Avenue street car near the site in the summer of 1875. The granite blocks seemed perfectly useful to Father Rosencrans. Deshon later examined the stone and purchased a large quantity of it, saving the budget around $22,000.

Nevertheless, within twelve months of the cornerstone laying ceremony on June 4, 1876, the project was $75,000 in debt. Construction ground to a halt.

Eventually funds came in and construction continued. But Father Young, who “was always inclined to do only just what his architect told him,” according to American Architect and Architecture, was unable to continue as supervisor and Father George Deshon was put in charge.

The periodical said “He was a very different sort of a man from Father Young, and knew all about masonry and heavy construction, having been the instructor in military engineering at West Point before he became a priest.”

Little by little O’Rourke found himself elbowed out. American Architect and Architecture said years later on July 27, 1910 that he “found himself in the awkward position of being instructed how to draw the plans on one side by the owner and having the owner also appear as chief of construction and superintendent of the work. His sphere of activity became more and more limited as time went on, until he finally was out altogether.” Jeremiah O’Rourke found himself in the role of draftsman, rather than architect.

Further humiliation to O’Rourke came as the last vestiges of his interior designs were erased by outside contractors. As the walls rose, three artists “came from time to time, in a friendly way, to see how the work went on, and, no doubt, to give advice,” said American Architect and Architecture. The trio consisted of Stanford White, John La Farge, and Augustus Saint Gaudens.

The last straw came when Father Deshon changed O’Rourke’s structural design of the roof trusses. The pair became involved in a heated stand-off that was settled when two experts were called in for consultation. They agreed with Deshon and Jeremiah O’Rourke returned across the Hudson River, leaving the project in the hands of Rev. George Deshon, now architect in charge as well as chief mechanic.

A decade after construction began, St. Paul the Apostle Church—known familiarly as the Church of the Paulists—was dedicated in January, 1885 on the Feast Day of St. Paul–even though the church was far from complete. Anticipation of the church’s opening was such that a week earlier The Sun held out little hope that late-comers would be admitted.

“The sale of seats at $2 and $1 for the mass and dedication, and for vespers at 7-1/2 in the evening at $1 and 50 cents, has been so large during the past week that it will probably be impossible to secure any at these prices after this afternoon and evening,” the newspaper reported on January 18.

Architectural critics at the time were hard-pressed to academically describe the structure. Marianna Griswold Van Rensselaer was unapologetic in her confusion. “I can hardly say with what ‘style’ one should rank this church. We may call it Gothic, if we will, since its openings are pointed, but it shows no window tracery and no Gothic decoration, and its broad wall-spaces remind us of very different fashions of construction. Whatever its ‘style,’ its effect will certainly not be that of an imitated medievalism.”

The New-York Tribune’s critic admired the somber design as opposed to some of the more flamboyant ecclesiastical structures, saying it “architecturally, lies in a vehement protest against the trumpery, voluptuous ideals now prevailing in fashionable church buildings.”

Oddly enough, King’s Views of New York City, A.D. 1903 called the 19th century structure, “Twentieth century Gothic architecture.”

Although dedicated, there was much work still to be done. Four years later the 94-foot tall church towers were still 20 feet short of completion. When demolition of the massive Egyptian Revival Croton Reservoir was initiated in 1899, the church fathers were once again on the scene to salvage granite. In a continuing program of recycling building materials, blocks of the old reservoir ended up at the highest points of the two towers.

The stone for the two grand flights of entrance steps, too, was salvaged. This granite came from the French Second Empire-style Booth’s Theatre on Sixth Avenue at 23rd Street. When Edwin Booth’s Shakespearean theater was converted to a department store, the blocks of granite removed from the structure were hauled north to 59th Street.

Completion of the interior decorations of the massive church would take decades. A virtual Who’s Who of American artists, architects and sculptors contributed to the space—John La Farge, Frederick MacMonnies, Robert Reid, Phillippe Martiny, William Laurel Harris, Bela Prat, La Marquise de Wentworth and Stanford White among them.

Nevertheless, the New-York Tribune was not necessarily impressed. On April 2, 1899 it complained that “The church erected by the Paulist Fathers at the northwest corner of Columbus-ave. and Fifty-ninth-st. has passed through vicissitudes in the matter of its architectural and decorative character. Begun in the seventies on a plan that in its rough outlines was not without merit, it rose under the supervision of divers hands, and hence failed to develop in a straight line. Good work was accompanied by work not at all good. To-day a considerable amount of the latter remains in one shape or another—some of the chapels in the aisles are far from being artistic—but during a number of years the influence of several authoritative artists has been gradually purging the edifice of its aesthetic errors.” The newspaper pointed out Stanford White’s two white marble altars, “in the pure and beautiful style of the Italian Renaissance” and Philip Martiny’s “graceful sanctuary lamp which sways above the chancel steps.” White was also responsible for main sanctuary lamps which The American Architect deemed “one of the finest specimens of bronze work of its kind in the United States.”

But two names rose to the top—John La Farge and William Laurel Harris. At the time of the article La Farge had just completed five large wall medallions and was responsible for the stained glass clerestory windows, the apse windows and the lancet windows at the rear of the church. He also designed the baptistery. He would continue decorating areas of the church for over a decade; completing a total of 23 windows and nine wall paintings.

William Laurel Harris had no end in sight when he took on the project of painting the frescoes. In 1910 American Architect said “The task which Mr. Harris has set himself is a life work, and, as far as may be ascertained, without a parallel in the history of American mural decoration.”

Two years later, on June 17, 1912, The Sun commented “What the decorations and enrichments of the Church of St. Paul the Apostle will cost or when they will be finished nobody pretends to say. William Laurel Harris, who is giving his life to the work of these embellishments, has just completed his fourteenth year there…With the backing of the Society of St. Paul, he is trying to do in art what the Paulists, directing themselves and others, have already done in music. That is, they are restoring the old Roman art in its application to ecclesiastical architecture.”

By 1973 the situation had become serious enough that demolition of St. Paul the Apostle was being discussed. Removal of the massive church would free up land that the church could sell for commercial development to make the parish “financially viable.”

The music to which the newspaper referred was the Gregorian chant—revived by the Paulist fathers in 1870 and developed by organist and choirmaster Edmund G. Hurley appointed a year later. In January 1894 Cardinal Satolli, Papal Delegate in the United States attended the choir’s celebration of the Feast of St. Paul. He wrote about the choir’s Gregorian chant, calling it “one of the most grateful impressions I retain of my last visit to New-York” and saying “May it please Almighty God that such edifying singing could be heard in all the churches of the country!”

In the meantime, decoration of the church continued. John La Farge had earlier completed a mural medallion on the north side of the apse “The Angel of the Sun.” A companion painting, “The Angel of the Moon” was completed in 1909 and received a medal from the Architectural League of New York. But before the latter work was installed, the artist died and, according to The Sun, “at the dispersal of Mr. La Farge’s art collection to adjust his estate it was purchased by the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences.”

In 1912 the steadily-laboring William Laurel Harris received the task of creating a new “Angel of the Moon.” His large “The Crucifixion” (55 feet long and 20 feet high) had been completed two years earlier, deemed by The Sun to be “the largest mural painting ever executed for the interior of a church in America.” The newspaper noted that “In preparation for this work the painter spent a year in Jerusalem.”

The forward thinking Paulist Fathers embraced the new technology of radio in the 1930s with the launching of radio station WLWL. The Airwaves of New York in 1938 noted that the Missionary Society of St. Paul the Apostle “installed studios and transmitter in the Church of St. Paul the Apostle…The 226-foot towers beside the rectory were likened to modern-day steeples.”

As the centennial of the founding of the Paulist Fathers neared in the 1950s, a massive exterior bas-relief mural was envisioned to mark the occasion. American illustrator and muralist Lumen Martin Winter was given the commission in 1958 for the 18-by-60-foot artwork above the center portal.

The 50-ton panel was executed in Pietrasanta, Italy with figures sculpted in brilliant white travertine marble which contrasted with the Venetian mosaic background in 15 blue and green hues. The depiction of St. Paul’s spiritual awakening was dedicated in December 1958.

Within only a few years the congregation was in trouble financially. By 1973 the situation had become serious enough that demolition of St. Paul the Apostle was being discussed. Removal of the massive church would free up land that the church could sell for commercial development to make the parish “financially viable.”

At the twelfth hour, the bottom dropped out of the real estate market. In 1975 a relieved New York Times architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable wrote “One of the city’s most impressive architectural white elephants, St. Paul the Apostle on Ninth Avenue, with a galaxy of ecclesiastical arts, has been kept out of the hands of developers only by the building recession.”

At the turn of the 21st century the church was cleaned and repointed. The massive church which resulted from a tangle of dissension and head-butting survives, a veritable museum of exquisite artwork.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Explore Houses of Worship

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the religious institution currently at 120 West 60th Street:

St. Paul the Apostle Church

Learn about ReUse at St. Paul the Apostle