120 Riverside Drive

by Tom Miller

As their luxurious new apartment building on the northeast corner of Riverside Drive and 84th Street received its finishing touches in June 1906, developers W. R. & J. M. Stewart advertised,

Housekeeping Apartments of 10 and 11 rooms and 3 bathrooms. Fireproof Building. Large, light rooms; all conveniences; best possible construction; ready for occupancy summer of 1906.

“Housekeeping apartments” meant that the suites–two per floor–had kitchens, unlike residential hotels.

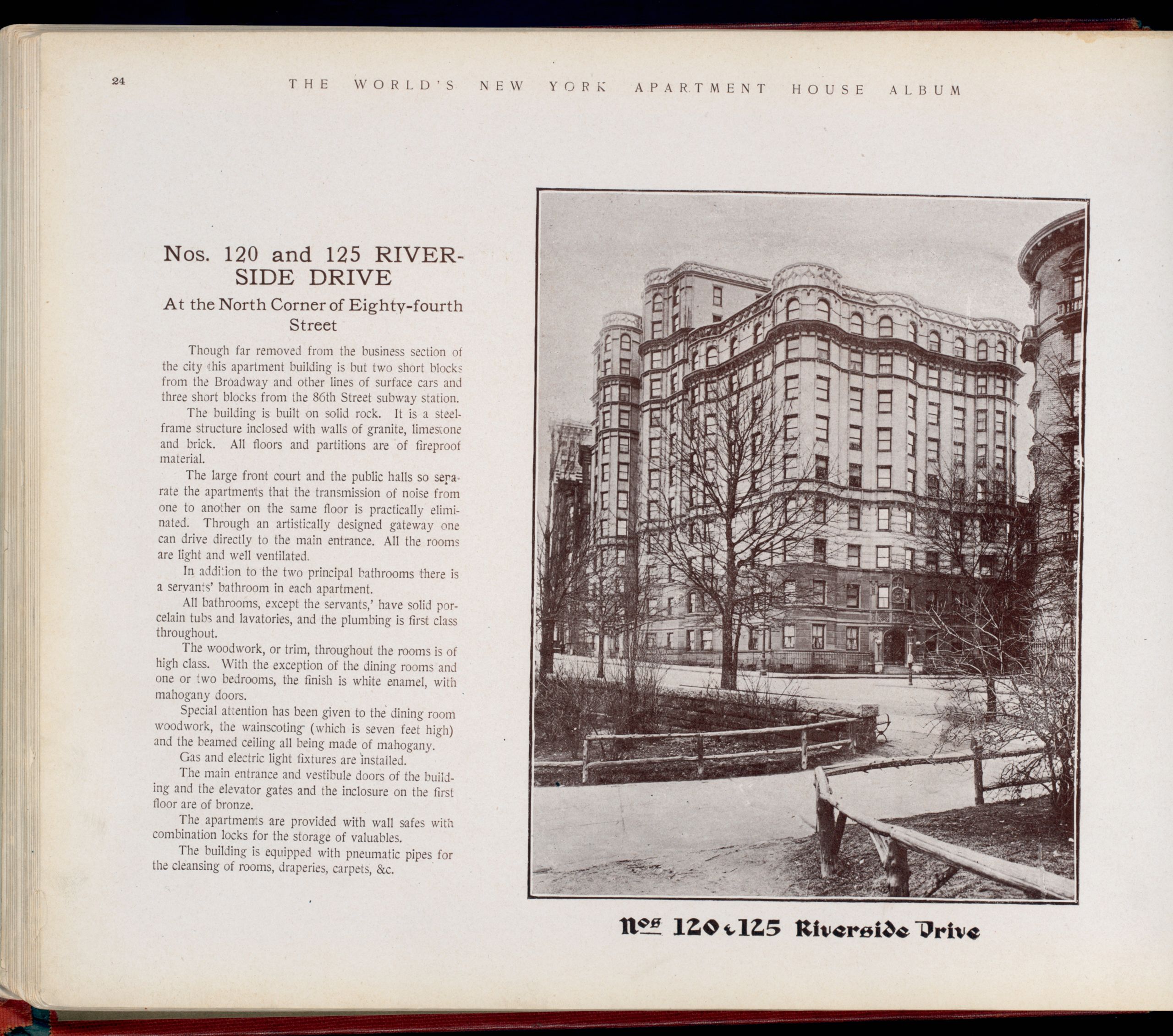

Designed by George Keister, the nine-story 120 Riverside Drive was faced in beige brick above a two-story limestone base. The architect’s neo-medieval design included Gothic corbels below the fourth- and ninth-floor cornices; four faceted, tower-like bays; and an intricate, pierced parapet. Keister lavished the entrance with medieval inspired carvings–Gothic tracery, flowers and vines, and a bas-relief of a woman surrounded by swirling faces of children and angels within a rondel.

The building’s tenants enjoyed amenities like seven-foot-high mahogany wainscoting and beamed ceilings in the dining rooms, built-in pneumatic-tube vacuums, and combination gas-and-electric lighting fixtures.

The first residents were its builders, brothers James M. and William R. Stewart. Their neighbors would be equally affluent and socially visible.

Among the earliest were the William Kellogg Tillotsons. Born in Owosso, Michigan to Norton and Wealthy Ann Tillotson in 1835, William married Helen Beach Brewster on September 8, 1861. Soon afterward, he left his bride to fight in the Civil War and earned the rank of first lieutenant. The couple had two sons, Norton Beach, born in 1863, and John Beach, born in 1874. Daughters Abby Kimball and Lucy Beach came in 1865 and 1867 respectively. Abby would never marry, and lived in the Riverside Drive apartment with her parents.

The New-York Tribune reported, “A south-bound car came along at high speed.

While Helen was active in civic issues, Abbie was more socially visible. On April 6, 1902, for instance, the New-York Tribune reported, “The Shakespeare Club of New-York City spent a social evening at the home of Miss A. R. [sic] Tillotson, No. 120 Riverside Drive, on Thursday.” The following year, on March 29, the newspaper reported, “An unusual dinner last night varied the monotony of Lent. Given by the Shakespeare Club, it began at the Beresford and ended at No. 120 Riverside Drive.” Guests started at the home of the John De Witt Warner’s for cocktails, and moved from place to place until ending the evening with “dessert and coffee provided by Mrs. [sic] Abbie Tillotson…Music finished the evening’s entertainment.”

In the meantime, Helen was active in the Women’s Health Protective and the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. When the National Arbitration and Peace Congress adjourned in New York City in April 1907, the American flag was lowered and entrusted to Helen. She presented it to Andrew Carnegie at the National Convention in Washington D.C. “in appreciation of his bountiful services to the holy cause of peace.”

Attorney Edward F. Coles and his wife were also early residents. Mrs. Coles left the apartment on June 22, 1902 and nearly did not return. She and Arthur Cole, the couple’s nephew, were in the Cole carriage when its driver, John Thatcher, attempted to cross the streetcar tracks at Sixth Avenue and 27th Street. The New-York Tribune reported, “A south-bound car came along at high speed. Dennis Curran, the motorman, applied his brake, but the car crashed into the coach, overturning it.”

Astoundingly, no one was seriously injured. Thatcher, of course, was propelled from his seat. The article said, “Although he landed heavily on the pavement, he escaped with slight injuries.” It continued, “Mrs. Cole and her nephew…were thrown headlong to the ground, but they too, escaped unhurt.”

William Robert Stewart and his wife, the former Almira Giffen, had three children, Myra, Irene and William, Jr. Like Helen Tillotson, Almira was a member of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She was also a regent of the Daughters of the Union. On November 19, 1914, she hosted a meeting of the latter group, at which artist Leonard M. Davis spoke on “Art and Alaska.” Although there was “a short business meeting,” the gathering was mostly social, including piano and musical solos. The New York Press noted, “A social hour will close the afternoon, the tea table to be presided over by Miss Irene Stewart and Miss Myra Stewart, the charming daughters of the regent.”

The 1911 Dau’s New York Blue Book of society was replete with residents of 120 Riverside Drive. Included, were, of course, James M. and Grace Pinney Stewart. Their son, who was named after his uncle, William Robert Stewart, was eight years old when the family moved into the building. Living with them were Grace’s widowed mother, Elsie Peach Simpson Pinney. (She died in the apartment at the age of 87 on August 13, 1911.)

Young William Stewart would enjoy a privileged upbringing. He would eventually attend the Taft School. Later, the athletic young man would play football, basketball and golf at Yale University, graduating in 1921.

Like her sister-in-law, Grace Stewart was active in civic causes. On May 18, 1916, for instance, The New York Press reported, “A meeting of the Woman’s League for the Protection of Riverside Park will be held in the residence of Mrs. James M. Stewart, No. 120 Riverside Drive, next Thursday.”

Montgomery Roosevelt Schuyler, Jr. lived here by 1911. His father was a cousin of Theodore Roosevelt, and his mother, Lydia Eliza Roosevelt was the daughter of Nicolas James Roosevelt and Lydia Sellon Latrobe. The Roosevelt-Schuyler connection was strengthened in March 1877 when he married Leila Roosevelt, the daughter of James Alfred Roosevelt and Elizabeth Norris Emlen. The Times of Philadelphia said, “The wedding was a fashionable event.”

Domestic bliss was relatively short-lived, however. Almost unheard of in society, on February 29, 1884, The Times reported that Leila had filed for a divorce. The article said, “She declares that her husband deserted her at their East Nineteenth street house at Christmas 1881, and has remained away ever since.”

Now single, Schuyler was a partner in the “whiskey importing firms of Roosevelt and Schuyler,” according to the Asbury Park Evening Press. His affluent lifestyle was reflected in his club memberships–among them the Holland Society, the Century, Manhattan, the Larchmont Yacht, and the New York Yacht Clubs. His country home was in Nyack, New York. The Asbury Park Evening Press said of him, “He owned some of the fastest pleasure yachts in eastern waters and engaged in the breeding of blooded horses.” Schuyler died at the age of 70 at his country home on New Year’s Day 1924.

Charles Lacy Craig was a partner in the law firm of Hoadley, Lauterbach & Johnson, an officer in the West End Association, and counsel for the West Side Improvement Association in 1913. Born on March 9, 1872, he was a 1903 graduate of Columbia University Law School. The New York Times later said, “He immediately married Miss May Josephine Creiver.” The couple moved into a third-floor apartment at 120 Riverside Drive. Their country home was in Carmel, New York.

The article said, “She declares that her husband deserted her at their East Nineteenth street house at Christmas 1881, and has remained away ever since.”

In 1917, Craig’s name became a household word after a face-off with Mayor John Purroy Mitchel. The administration was behind a push “to beautify Riverside Drive Park by covering the New York Central’s tracks and extending the park to the water’s edge.” Craig testified on February 17 that the “improvement” would involved widening the park by a mere six inches and calling it a playground, while giving the New York Central additional track space.

The New York Times reported that Mitchel “officially called Craig ‘a deliberate, malicious and vicious liar.'” The attorney responded by inviting the Mayor to “come out into City Hall Park and repeat that.” Charles F. Murphy, the current head of Tammany Hall, was overjoyed at Craig’s bravado and asked the attorney to come see him.

In the next election, John Francis Hylan became mayor, and Craig was appointed comptroller. It was beginning of a meteoric public career. So public was Craig’s life, in fact, that on January 22, 1920, the New York Herald ran a headline that read, “Comptroller Craig Has a Cold.”

An incident more frightening than a cold had occurred in the Craig apartment three months earlier. A mysterious package was delivered on October 27, 1919 “bearing foreign stamps and mail labels,” according to the New-York Tribune. The article said May “notified the Bureau of Explosives that it looked suspicious.” Inspector Owen Egan arrived and carefully opened the parcel. The New-York Tribune reported, “It was found to contain eight fancy plates sent from Austria by a friend of the Craig family serving with the American army.”

At some point prior to 1941, the unique parapet was removed. Then, a renovation completed in 1956 slightly reduced the size of the apartments on floors three through six. There were now three apartments per floor on those levels.

George Keister’s 1906 romantic take on medieval design continues to be home to well-to-do residents. Despite the loss of its parapet, and while an unfortunate iron fire escape detracts from the architecture, 120 Riverside Drive survives greatly intact.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com