103 Riverside Drive

by Tom Miller

As the 19th century came to a close, developers were busy building luxurious row houses along the new Riverside Drive. The breathtaking views of the Hudson River and the palisades on the opposite shore created spectacular vistas. Yet not all of the wealthy New Yorkers who settled here would be among the inner-most circle of high society.

Decades later the Works Progress Administration’s New York City Guide would say “Riverside Drive, like Wall Street, is a national symbol of wealth, but unlike Wall Street, it has never quite deserved its reputation. From the 1890s until after the World War, to be sure, it was popular with the newly rich, whose ornate gray and brownstone battlemented houses bore witness to economic success; yet, lacking an old-family tradition, it never rivaled streets like Fifth Avenue in the esteem of fashionable society.”

Among those gray and brownstone houses were six quaint residences designed and built by Clarence F. True between 1898 and 1899 between 83rd and 84th Streets, with financial help from famous actor Joseph Jefferson. True developed much of Riverside Drive on a speculative basis and his use of historic styles became his hallmark. While the design of each of these Elizabethan Revival-style houses was individual, they flowed cohesively, creating a charming row. True received permission from the Commissioner of Buildings in 1898 to build over the property lines, resulting in an undulation of bowed fronts and projecting porches.

In the midst of the row was 103 Riverside Drive, an L-shaped five-story mansion with a steep tile roof, a side courtyard (a rare luxury in the city), and a deep bowfront.

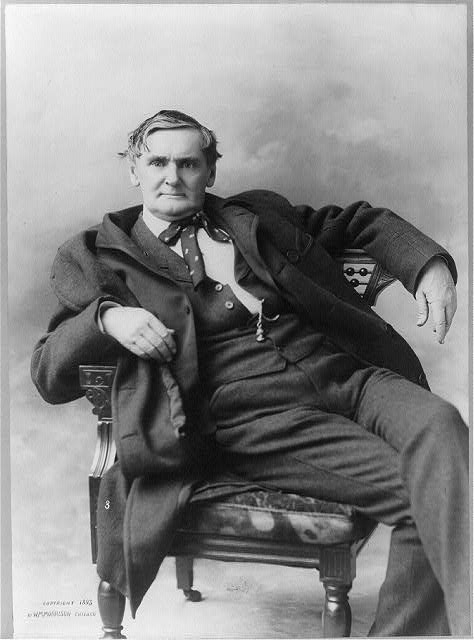

Jefferson, who is widely credited with first saying “There are no small parts, only small actors,” is also remembered in the nicknaming of The Church of the Transfiguration as “The Little Church Around the Corner.”

On April 23, 1902, Joseph Jefferson purchased the house for $40,000 in foreclosure actions against True. Jefferson, who is widely credited with first saying “There are no small parts, only small actors,” is also remembered in the nicknaming of The Church of the Transfiguration as “The Little Church Around the Corner.” In 1870 when Jefferson tried to arrange the funeral for his actor friend George Holland at, presumably, Marble Collegiate Church, he was rebuffed because of the deceased’s profession. Being told that there was a little church around the corner “where they do that sort of thing,” Jefferson replied “God bless the little church around the corner.”

The actor sold the house in 1906 to financier Elbridge Gerry Snow, Jr. and his wife Maud. Snow doubtlessly regretted the purchase when Charlotte Y. Ackerman, who owned the lot just south of the row, won a court case in which she argued that the projecting bowfronts and porches encroached on the public street and lowered her property value.

The courts ruled that the owners had to remove the fronts of their homes. Snow commissioned architects Clinton & Russell to design a new façade, using the materials from the demolished original. Completed in 1911, the new front was a flat, ironspot brick wall with limestone trim. The architects retained the original flavor of True’s design by including the arched, recessed entranceway, the original second story windows and the arched fourth-story windows and keystones. The cornice was nearly identical and the peaked red tile roof was salvaged. A ground-floor arched service entrance was installed where the courtyard wall had been.

Shortly after the renovations were completed, the title was transferred to actress Amelia Bingham. The feisty and colorful Bingham, a favorite on the New York stage, set about sprucing up the outside of the mansion. On two small balconies above the first floor (now gone) she perched three heroic-sized statues and two large busts–the one directly over the entrance being of Shakespeare. The redecoration prompted The New York Times to call it “one of the really unique residences in the city.” It became a sightseeing attraction–popularly called “the house with the statues.”

In 1916, the New York Central Railway proposed laying tracks below Riverside Drive along the Hudson. Amelia Bingham was enraged. She hosted a meeting of the Woman’s League for the Protection of Riverside Park within her parlor.

The actress was firm. “We must turn to these splendid men–oh, let’s say they’re splendid, anyway—and tell them to have mercy on our happiness…But if they persist I shall sell my home for what I can get and move where I won’t have to listen to steam shovels for ten years, for, I tell you, there are lots of us who can’t wait the generation it will take the trees to grow again in our beautiful front yard.”

At another meeting, Bingham pleaded, “For all these years I have loved to sit in my front window and get drunk with the beauty of Riverside Park. I have lived on the Thames, on the Seine, on the Rhine, and always come home to get drunk again on the glory of Riverside Park.”

A year later, Bingham was in danger of losing her view not because of the New York Central Railway but because her home was in foreclosure. The actress had failed to pay a second mortgage of $25,000 and, when the actress was ordered to vacate the property or pay rent of $250 per month, she refused to do either.

In 1942, the storied house, which boasted a self-service elevator, was sold for $14,000 cash–the amount of the outstanding mortgage.

The crisis passed, but in 1925, more drama visited Amelia Bingham in her Riverside Drive home. Two young robbers gained entrance and forced the maid at gunpoint to lead them upstairs. There Bingham, her seamstress, and her maid were bound with silk stockings while the robbers ransacked her bedroom, making off with $1,500 of jewelry and valuables.

In the meantime, the quick-witted Amelia sat on a bag containing $20,000 in cash and valuables and chatted casually with the thieves to distract them. It was “just like the stage,” she explained later when questioned on her cool-headedness.

The remarkable actress died in the house on September 1, 1927 and the following year her sisters sold it. Dr. John A. Harriss, the Special Deputy Police Commissioner in charge of traffic moved in. An authority on street traffic problems, he invented the traffic signal light system and came up with the innovative idea of one-way streets. Dr. Harris died of a heart attack in the house in October 1938.

In 1942, the storied house, which boasted a self-service elevator, was sold for $14,000 cash–the amount of the outstanding mortgage. At the time, the house was assessed at $32,000, $27,000 of which was land value.

No. 103 Riverside Drive managed to escape being divided into apartments, although its interiors have been highly altered. In November 1997, the house was purchased for just under $13.5 million by financier Richard Schneider and his wife Tami.

In 2010, the amazing and unique home with its colorful past was put on the market for $21.5 million before being taken off a few months later.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com